50

Georg Baselitz

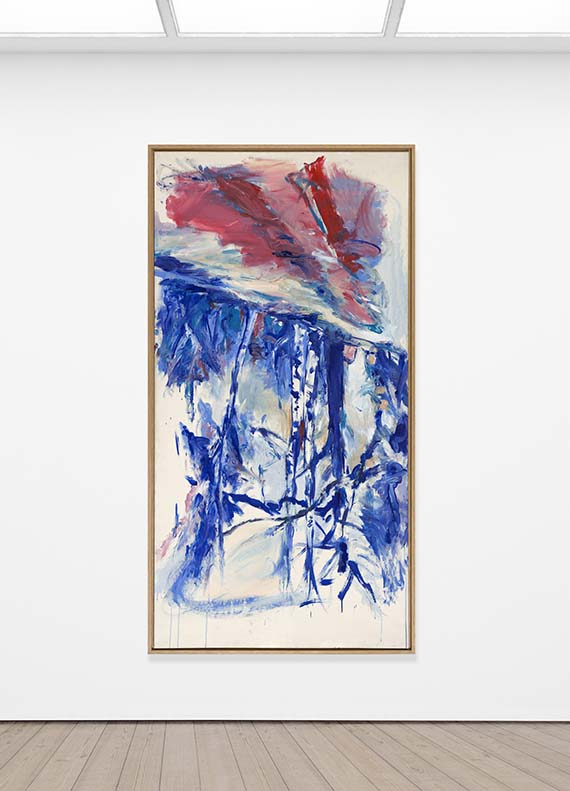

Waldweg, 1974.

Oil on canvas

Estimation:

€ 700,000 / $ 826,000 Résultat:

€ 1,345,000 / $ 1,587,100 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

50

Georg Baselitz

Waldweg, 1974.

Oil on canvas

Estimation:

€ 700,000 / $ 826,000 Résultat:

€ 1,345,000 / $ 1,587,100 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

Waldweg. 1974.

Oil on canvas.

Lower right signed and dated. 190 x 97 cm (74.8 x 38.1 in).

• In the picture "Der Wald auf dem Kopf" (Forest Upside-Down ) from 1969, today at Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Baselitz rotated the image by 180 degrees for the very first time.

• Works like "Waldweg“ (1974) from the series of the "Fingermalerei" (Finger Painting) are extremely rare and realize top prices on the international auction market.

• Georg Baselitz donated six pictures from the late 1960s to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In 2021 they were part of the exhibition "Georg Baselitz. Pivotal Turn".

• Currently (October 2021 - March 2022), the Centre Pompidou in Paris honors Georg Baselitz with a comprehensive retrospective show.

• A personal gift from Baselitz to his artist friend A. R. Penck.

PROVENANCE: A.R. Penck (as present from the artist.

Galerie Onnach, Berlin.

First Bank, Minneapolis.

Jan Eric Löwenadler, New York/ Stockholm.

Private collection Hamburg.

Galerie Ropac, Salzburg.

Private collection Northern Germany.

EXHIBITION: Georg Baselitz: Paintings Bilder 1962-1988, Runkel-Hue-Williams, Ltd./ Grob Gallery, London, September 19 - November 2. 1990, pp. 36/ 37 (color illu.) and p. 70 (black-and-white illu.).

Andere Ansichten, Galerie Terminus, Munich, January- February 2005.

Georg Baselitz, Vonderbank Artgalleries, Berlin, March 17 - April 26, 2006, p. 10 (with illu.)

Georg Baselitz. Arbeiten aus europäischen Sammlungen, Galerie Michael Werner, Cologne, November 9 - January 11, 2020, cat. no. 38 (with illu.)

Georg Baselitz. I Was Born into a Destroyed Order, Michael Werner Gallery, London, September 11 - December 5, 2020, cat. no. 23, pp. 48/ 49 (with illu.).

LITERATURE: Christie' s, London, October 24, 1996, lot 119.

Sotheby' s, New York, November 14, 2012, lot 334.

"The hierarchy that places heaven at the top and earth at the bottom is just a convention anyway. We've gotten used to them, but we don't have to believe in them. The only thing that interests me is the question of how I can continue to paint pictures."

Georg Baselitz

Oil on canvas.

Lower right signed and dated. 190 x 97 cm (74.8 x 38.1 in).

• In the picture "Der Wald auf dem Kopf" (Forest Upside-Down ) from 1969, today at Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Baselitz rotated the image by 180 degrees for the very first time.

• Works like "Waldweg“ (1974) from the series of the "Fingermalerei" (Finger Painting) are extremely rare and realize top prices on the international auction market.

• Georg Baselitz donated six pictures from the late 1960s to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In 2021 they were part of the exhibition "Georg Baselitz. Pivotal Turn".

• Currently (October 2021 - March 2022), the Centre Pompidou in Paris honors Georg Baselitz with a comprehensive retrospective show.

• A personal gift from Baselitz to his artist friend A. R. Penck.

PROVENANCE: A.R. Penck (as present from the artist.

Galerie Onnach, Berlin.

First Bank, Minneapolis.

Jan Eric Löwenadler, New York/ Stockholm.

Private collection Hamburg.

Galerie Ropac, Salzburg.

Private collection Northern Germany.

EXHIBITION: Georg Baselitz: Paintings Bilder 1962-1988, Runkel-Hue-Williams, Ltd./ Grob Gallery, London, September 19 - November 2. 1990, pp. 36/ 37 (color illu.) and p. 70 (black-and-white illu.).

Andere Ansichten, Galerie Terminus, Munich, January- February 2005.

Georg Baselitz, Vonderbank Artgalleries, Berlin, March 17 - April 26, 2006, p. 10 (with illu.)

Georg Baselitz. Arbeiten aus europäischen Sammlungen, Galerie Michael Werner, Cologne, November 9 - January 11, 2020, cat. no. 38 (with illu.)

Georg Baselitz. I Was Born into a Destroyed Order, Michael Werner Gallery, London, September 11 - December 5, 2020, cat. no. 23, pp. 48/ 49 (with illu.).

LITERATURE: Christie' s, London, October 24, 1996, lot 119.

Sotheby' s, New York, November 14, 2012, lot 334.

"The hierarchy that places heaven at the top and earth at the bottom is just a convention anyway. We've gotten used to them, but we don't have to believe in them. The only thing that interests me is the question of how I can continue to paint pictures."

Georg Baselitz

The inversion of the usual

When Georg Baselitz turned “Der Wald auf dem Kopf” (The Foret upside down) around in 1969 - the first time ever that he rotated a motif by 180 degrees, it was perceived as an artistic provocation by many. Without question, he wanted to radically question the act of painting itself, but also traditional viewing habits, but a provocation as an end in itself is not the artist‘s style. He takes painting too seriously, its long history and the enormous potential it bears. Later Baselitz said that at that time he had reached a point where he wanted to change the direction of his painting. As early as in 1964 he was experimenting with rotated motifs, as the painting "Das Kreuz“ (The Cross) delivers proof of: In a small scene, Baselitz turned the row of houses upside down. And in 1968 he tied a forest worker upside down to a tree in the painting of the same name, certainly a reminiscence of the martyrdom of the Apostle Peter and the Christian world of motifs from Renaissance. The following year he painted “Der Wald auf dem Kopf“, the first composition in which the motif is completely upside down. The artist was probably inspired by the painting "Wermsdorfer Wald" by Ferdinand von Rayski (1806-1890) from 1859 in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie Neue Meister. And with this inversion in the picture, Baselitz ultimately combines a deeply Nordic romanticism with the impulsiveness of German Expressionism, both in terms of art history and painting.

From then on, the upside-down motif will dominate the artist's work, a form of "abstraction" without a doubt, but in which the subject is not lost. The inversion was not only a revolutionary act in the truest sense of the word, but also a means by which Baselitz could concentrate on abstract qualities. “The problem for me was not creating anecdotal, descriptive images. On the other hand, I always hated the nebulous arbitrariness of the theory of non-representational painting. Reversing the motif in the picture gave me the freedom to deal with painterly problems,” says Baselitz (quoted from: Siegfried Gohr, Über Baselitz. Aufsätze und Gespräche, Cologne 1996, p. 60). And elsewhere, Baselitz becomes even more clear when he was asked why he turned the motifs upside down: “The object does not express anything. Painting is not a means to an end. On the contrary, painting is autonomous. And I said to myself: If that's the case, then I have to take everything that has been the subject of painting so far - the landscape, the portrait, the nude, for example - and turn it around. That is the best way to free the presentation from the content” (quoted from: Franz Dahlem, Georg Baselitz, Cologne 1990, p. 88).

Attacking the illusion of painting

The upside-down paintings by Baselitz show a radical departure from the mimesis of Western painting, from the conventions of painting, which go back to the rules of perspective developed in Renaissance. The illusion that the viewer of a painting sees an accurate representation of the world lasted well into the later 19th century, when photography replaced the painted magic with a more convincing representation of the real world. Since that time, painters have been creating illusions about what they see in a different way, developing painting styles such as Impressionism, losing themselves in the theory of Pointillism and unfolding their full potential in Expressionism and New Objectivity, and finally trying their hand at the broad field of the non-representational. And yet, like many painters of the 20th century, Baselitz was looking for a way to break with the tradition of painting pictures without sacrificing the appearance of reality. And Baselitz convincingly challenges his viewers to accept his upside-down world as a new pictorial convention. The picture painted “upside down” is accompanied by the effect of removing meaning from the figure, freeing the motif from a certain gravity. After this "turning point" in 1969, Baselitz painted a series of upside-down portraits, followed by pictures within a picture, in which one picture - usually a landscape - was framed by another, thus continuing the break with conventional painting.

The motif. The forest

In 1971 the artist moved to Forst an der Weinstraße and then on to Derneburg in 1975. Baselitz continued to experiment and look for ways to design his characteristic motifs in form, color and surface using various techniques that did not stand in the way of either the subject or the painting style. In his new studio, surrounded by nature, the first finger paintings were created. The distancing from the motif goes hand in hand with a physical approach to painting. Baselitz dips his hands into the paint and uses his fingers to transfer the image directly onto the canvas. Nothing should stand between him and the painting, not even the brush. In the years to come, outstanding works with an unprecedented character were created, such as "Fingermalerei I - Adler" (1971/72), "Akt Elke" (1974) and the furiously painted "Waldweg", a vivid but fragmentary motif with neither a concrete narrative or content. One of the early finger paintings, "Fingermalerei - Birken", from 1972, was on display at documenta 5 the year it was painted.

In the painting "Waldweg“ (Forest Path) we see an avenue of birch trees in cobalt blue and an intense red on a slim elongated canvas. The rather unusual dimensions of the image carrier itself (190 x 97 cm) convey the feeling of a narrow forest path, along which the tall and slender birch trees grow. The artist's hand remains visible and occasionally his fingers show through the depiction in sweeping gestures, dissolving the twisted form into abstraction. The radical effect of the motif reversal can be felt when the image is rotated 180 degrees back to its natural orientation. The floating forest path, which has no references to any location, immediately changes into a steeply ascending path that conveys the heaviness and exertion of a tedious hike. Taking a second look at "Waldweg", however, the lightness of the depiction of the birch trees compared to the density of the forest path reveals a hidden symbolism: a charged mythological-religious iconography of the tree. However, Baselitz does not just leave it at the persuasiveness of the painterly. The “inversion” also opens up metaphysical, philosophical and conceptual levels of meaning for the artist. [MvL/SN]

When Georg Baselitz turned “Der Wald auf dem Kopf” (The Foret upside down) around in 1969 - the first time ever that he rotated a motif by 180 degrees, it was perceived as an artistic provocation by many. Without question, he wanted to radically question the act of painting itself, but also traditional viewing habits, but a provocation as an end in itself is not the artist‘s style. He takes painting too seriously, its long history and the enormous potential it bears. Later Baselitz said that at that time he had reached a point where he wanted to change the direction of his painting. As early as in 1964 he was experimenting with rotated motifs, as the painting "Das Kreuz“ (The Cross) delivers proof of: In a small scene, Baselitz turned the row of houses upside down. And in 1968 he tied a forest worker upside down to a tree in the painting of the same name, certainly a reminiscence of the martyrdom of the Apostle Peter and the Christian world of motifs from Renaissance. The following year he painted “Der Wald auf dem Kopf“, the first composition in which the motif is completely upside down. The artist was probably inspired by the painting "Wermsdorfer Wald" by Ferdinand von Rayski (1806-1890) from 1859 in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie Neue Meister. And with this inversion in the picture, Baselitz ultimately combines a deeply Nordic romanticism with the impulsiveness of German Expressionism, both in terms of art history and painting.

From then on, the upside-down motif will dominate the artist's work, a form of "abstraction" without a doubt, but in which the subject is not lost. The inversion was not only a revolutionary act in the truest sense of the word, but also a means by which Baselitz could concentrate on abstract qualities. “The problem for me was not creating anecdotal, descriptive images. On the other hand, I always hated the nebulous arbitrariness of the theory of non-representational painting. Reversing the motif in the picture gave me the freedom to deal with painterly problems,” says Baselitz (quoted from: Siegfried Gohr, Über Baselitz. Aufsätze und Gespräche, Cologne 1996, p. 60). And elsewhere, Baselitz becomes even more clear when he was asked why he turned the motifs upside down: “The object does not express anything. Painting is not a means to an end. On the contrary, painting is autonomous. And I said to myself: If that's the case, then I have to take everything that has been the subject of painting so far - the landscape, the portrait, the nude, for example - and turn it around. That is the best way to free the presentation from the content” (quoted from: Franz Dahlem, Georg Baselitz, Cologne 1990, p. 88).

Attacking the illusion of painting

The upside-down paintings by Baselitz show a radical departure from the mimesis of Western painting, from the conventions of painting, which go back to the rules of perspective developed in Renaissance. The illusion that the viewer of a painting sees an accurate representation of the world lasted well into the later 19th century, when photography replaced the painted magic with a more convincing representation of the real world. Since that time, painters have been creating illusions about what they see in a different way, developing painting styles such as Impressionism, losing themselves in the theory of Pointillism and unfolding their full potential in Expressionism and New Objectivity, and finally trying their hand at the broad field of the non-representational. And yet, like many painters of the 20th century, Baselitz was looking for a way to break with the tradition of painting pictures without sacrificing the appearance of reality. And Baselitz convincingly challenges his viewers to accept his upside-down world as a new pictorial convention. The picture painted “upside down” is accompanied by the effect of removing meaning from the figure, freeing the motif from a certain gravity. After this "turning point" in 1969, Baselitz painted a series of upside-down portraits, followed by pictures within a picture, in which one picture - usually a landscape - was framed by another, thus continuing the break with conventional painting.

The motif. The forest

In 1971 the artist moved to Forst an der Weinstraße and then on to Derneburg in 1975. Baselitz continued to experiment and look for ways to design his characteristic motifs in form, color and surface using various techniques that did not stand in the way of either the subject or the painting style. In his new studio, surrounded by nature, the first finger paintings were created. The distancing from the motif goes hand in hand with a physical approach to painting. Baselitz dips his hands into the paint and uses his fingers to transfer the image directly onto the canvas. Nothing should stand between him and the painting, not even the brush. In the years to come, outstanding works with an unprecedented character were created, such as "Fingermalerei I - Adler" (1971/72), "Akt Elke" (1974) and the furiously painted "Waldweg", a vivid but fragmentary motif with neither a concrete narrative or content. One of the early finger paintings, "Fingermalerei - Birken", from 1972, was on display at documenta 5 the year it was painted.

In the painting "Waldweg“ (Forest Path) we see an avenue of birch trees in cobalt blue and an intense red on a slim elongated canvas. The rather unusual dimensions of the image carrier itself (190 x 97 cm) convey the feeling of a narrow forest path, along which the tall and slender birch trees grow. The artist's hand remains visible and occasionally his fingers show through the depiction in sweeping gestures, dissolving the twisted form into abstraction. The radical effect of the motif reversal can be felt when the image is rotated 180 degrees back to its natural orientation. The floating forest path, which has no references to any location, immediately changes into a steeply ascending path that conveys the heaviness and exertion of a tedious hike. Taking a second look at "Waldweg", however, the lightness of the depiction of the birch trees compared to the density of the forest path reveals a hidden symbolism: a charged mythological-religious iconography of the tree. However, Baselitz does not just leave it at the persuasiveness of the painterly. The “inversion” also opens up metaphysical, philosophical and conceptual levels of meaning for the artist. [MvL/SN]