Video

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

10

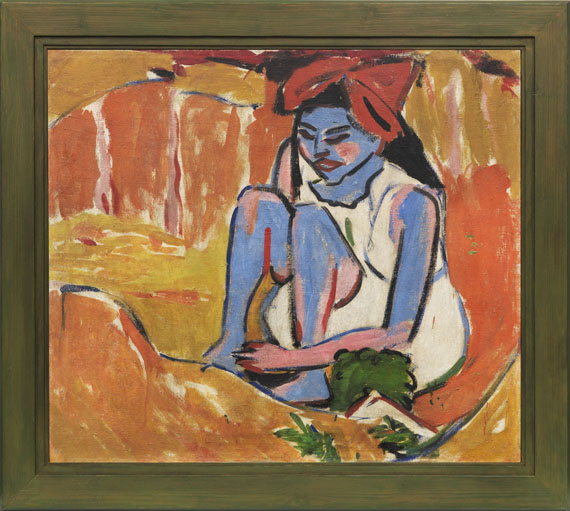

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Das blaue Mädchen in der Sonne, 1910.

Oil on canvas

Estimation:

€ 2,000,000 / $ 2,360,000 Résultat:

€ 4,750,000 / $ 5,605,000 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

10

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Das blaue Mädchen in der Sonne, 1910.

Oil on canvas

Estimation:

€ 2,000,000 / $ 2,360,000 Résultat:

€ 4,750,000 / $ 5,605,000 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

Das blaue Mädchen in der Sonne. 1910. Verso: Gelbgrüner Halbakt, 1910/1926.

Oil on canvas.

Gordon 139 and Gordon 139v. Signed and dated "06" in lower left on the reverse. 82.5 x 92.5 cm (32.4 x 36.4 in).

• A masterpiece of German Expressionism.

• Highlight in Hermann Gerlinger's renowned collection of "Brücke" art.

• E. L. Kirchner's two main models – Fränzi and Dodo – united on one canvas.

• The ingeniously reduced, powerful and high-contrast coloring makes this painting a solitaire within the artist's creation.

• Today paintings of this quality are almost exclusively museum-owned.

This work is documented at the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern.

PROVENANCE: From the artist's estate (Davos 1938, Kunstmuseum Basel 1946).

Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett Roman Norbert Ketterer, Stuttgart (1954).

Collection Rüdiger Graf von der Goltz, Düsseldorf (acquired in 1957).

Galerie Grosshennig, Düsseldorf (1961).

Collection Franz Westhoff, Düsseldorf (acquired from the above in 1961).

Wolfgang Wittrock Kunsthandel, Düsseldorf (acquired from the above in 1988).

Private collection USA (acquired from the above in 1988).

Wolfgang Wittrock Kunsthandel, Düsseldorf (reacquired from the above in 1990).

Collection Hermann Gerlinger, Würzburg (acquired from the above in an exchange in 1990, with the collector's stamp Lugt 6032).

EXHIBITION: Brücke 1905-1913, eine Künstlergemeinschaft des Expressionismus, Museum Folkwang, Essen, October 12 - December 14, 1958, cat. no. 52 (with the date "1905/06").

Meisterwerke der Malerei und Plastik des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, Galerie Wilhelm Grosshennig, Düsseldorf, March 20 - May 15, 1961, p. 3 (with illu.).

Schleswig-Holsteinisches Landesmuseum, Schloss Gottorf, Schleswig (permanent loan from the Collection Hermann Gerlinger, 1995-2001).

Frauen in Kunst und Leben der "Brücke“, Schleswig-Holsteinisches Landesmuseum, Schloss Gottorf, Schleswig, September 10 - November 5, 2000, cat. no. 50 (with illu. on p. 137).

Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle an der Saale (permanent loan from the Collection Hermann Gerlinger, 2001-2017).

Die Brücke in Dresden. 1905-1911, Dresdner Schloss, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Galerie Neue Meister, October 20, 2001 - January 6, 2002, cat. no. 172 (with illu. on p. 169).

Die Brücke und die Moderne, 1904-1914: an exhibition at the Bucerius-Kunst-Forum, Hamburg, October 17, 2004 - January 23, 2005, cat. no. 138 (with illu. on p. 163).

Expressiv! Die Künstler der Brücke. Die Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Albertina Vienna, June 1 - August 26, 2007, cat. no. 143 (with color illu. on p. 227).

Der Blick auf Fränzi und Marzella. Zwei Modelle der Brücke-Künstler Heckel, Kirchner und Pechstein, Sprengel Museum, Hanover, August 29, 2010 - January 9, 2011; Stiftung Moritzburg, Kunstmuseum des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle (Saale), February 6 - May 1, 2011, cat. no. 74 (with illu. on p. 227).

Im Farbenrausch. Munch, Matisse und die Expressionisten, Museum Folkwang, Essen, 2012-2013, cat. no. 69 (with illu. on p. 188).

Buchheim Museum, Bernried (permanent loan from the Collection Hermann Gerlinger, 2017-2022).

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Erträumte Reisen, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, November 16, 2018 - March 3, 2019, cat. no. 7, p. 36 (with illu. on plate 7).

LITERATURE: From the estate of Donald E. Gordon, University of Pittsburgh, Gordon Papers, series I., subseries 1, box 1, folder 140.

Donald E. Gordon, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Mit einem kritischen Katalog sämtlicher Gemälde, Munich/Cambridge 1968, p. 69 and 294, cat. no. 139 and 139 v (with illu. on p. 294 and p. 430).

Documentation of the 1958 exhibition, Archive Museum Folkwang, Essen, MF00084, l. 1f.; MF00085b, l. 1-4.

Ein Leben mit der Kunst, Wilhelm Grosshennig, Chemnitz 1921-1930, Düsseldorf 1951-1983 and 1986 (with color illu.).

Wolfgang Wittrock Kunsthandel, Gemälde, Aquarelle, Zeichnungen, Graphik. Künstler der Brücke und weitere Neuerwerbungen (catalog Wolfgang-Wittrock-Kunsthandel, no. 8), Düsseldorf 1988 (with illu.

Heinz Spielmann (ed.), Die Maler der Brücke. Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Stuttgart 1995, p. 259, p. 150, SHG no. 145 (with illu. on p. 151).

Michael Stitz, Interview mit Hermann Gerlinger, in: Vernissage. Die Zeitschrift zur Ausstellung, no. 4, 1995, pp. 22-25 (with illu. on p. 25).

Antje Wendt, Kunst geniessen. Reise zu Gemäldesammlungen in Schleswig-Holstein, 1999, pp. 62-69 (with illu.).

David Rosenberg, Art Game Boo. Histoire des arts du XXe Siècle, Paris 2003 (with illu.).

Heinz Spielmann, Die Brücke und die Moderne 1904-1914, in: Vernissage Nord, Ausstellungen Herbst/Winter, 2004/05, pp. 4-11 (with illu.).

Gerhard Presler, Die große Dresdner Kunstrevolte, in: Art, no. 4, 2005, pp. 26-40 (with illu.).

Hermann Gerlinger, Katja Schneider (eds.), Die Maler der Brücke. Inventory catalog Collection Hermann Gerlinger, Halle (Saale) 2005, p. 314, SHG no. 710 (with illu.).

Oskar Matzel, Von der Elbe an die Spree, in: Meike Hoffmann, Andreas Hüneke and Tobias Teumer (eds.), Festschrift für Wolfgang Wittrock. Zum 65. Geburtstag, no. 155, Freie Universität, Berlin 2012, pp. 16-18 (with illu. on p. 272, no. 10).

Inge Herold, Ulrike Lorenz and Thorsten Sadowsky (eds.), Wolfgang Henze, Verzeichnis der doppelseitig bemalten Gemälde Ernst Ludwig Kirchners, 2015, cat. no. D21 (with illu. on p. 149).

Brückenschlag: Gerlinger – Buchheim! Museumsführer durch die "Brücke"-Sammlungen von Hermann Gerlinger und Lothar-Günther Buchheim, Bernried 2017, p. 200 (with illu. on p. 201).

Oil on canvas.

Gordon 139 and Gordon 139v. Signed and dated "06" in lower left on the reverse. 82.5 x 92.5 cm (32.4 x 36.4 in).

• A masterpiece of German Expressionism.

• Highlight in Hermann Gerlinger's renowned collection of "Brücke" art.

• E. L. Kirchner's two main models – Fränzi and Dodo – united on one canvas.

• The ingeniously reduced, powerful and high-contrast coloring makes this painting a solitaire within the artist's creation.

• Today paintings of this quality are almost exclusively museum-owned.

This work is documented at the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern.

PROVENANCE: From the artist's estate (Davos 1938, Kunstmuseum Basel 1946).

Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett Roman Norbert Ketterer, Stuttgart (1954).

Collection Rüdiger Graf von der Goltz, Düsseldorf (acquired in 1957).

Galerie Grosshennig, Düsseldorf (1961).

Collection Franz Westhoff, Düsseldorf (acquired from the above in 1961).

Wolfgang Wittrock Kunsthandel, Düsseldorf (acquired from the above in 1988).

Private collection USA (acquired from the above in 1988).

Wolfgang Wittrock Kunsthandel, Düsseldorf (reacquired from the above in 1990).

Collection Hermann Gerlinger, Würzburg (acquired from the above in an exchange in 1990, with the collector's stamp Lugt 6032).

EXHIBITION: Brücke 1905-1913, eine Künstlergemeinschaft des Expressionismus, Museum Folkwang, Essen, October 12 - December 14, 1958, cat. no. 52 (with the date "1905/06").

Meisterwerke der Malerei und Plastik des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, Galerie Wilhelm Grosshennig, Düsseldorf, March 20 - May 15, 1961, p. 3 (with illu.).

Schleswig-Holsteinisches Landesmuseum, Schloss Gottorf, Schleswig (permanent loan from the Collection Hermann Gerlinger, 1995-2001).

Frauen in Kunst und Leben der "Brücke“, Schleswig-Holsteinisches Landesmuseum, Schloss Gottorf, Schleswig, September 10 - November 5, 2000, cat. no. 50 (with illu. on p. 137).

Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle an der Saale (permanent loan from the Collection Hermann Gerlinger, 2001-2017).

Die Brücke in Dresden. 1905-1911, Dresdner Schloss, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Galerie Neue Meister, October 20, 2001 - January 6, 2002, cat. no. 172 (with illu. on p. 169).

Die Brücke und die Moderne, 1904-1914: an exhibition at the Bucerius-Kunst-Forum, Hamburg, October 17, 2004 - January 23, 2005, cat. no. 138 (with illu. on p. 163).

Expressiv! Die Künstler der Brücke. Die Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Albertina Vienna, June 1 - August 26, 2007, cat. no. 143 (with color illu. on p. 227).

Der Blick auf Fränzi und Marzella. Zwei Modelle der Brücke-Künstler Heckel, Kirchner und Pechstein, Sprengel Museum, Hanover, August 29, 2010 - January 9, 2011; Stiftung Moritzburg, Kunstmuseum des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle (Saale), February 6 - May 1, 2011, cat. no. 74 (with illu. on p. 227).

Im Farbenrausch. Munch, Matisse und die Expressionisten, Museum Folkwang, Essen, 2012-2013, cat. no. 69 (with illu. on p. 188).

Buchheim Museum, Bernried (permanent loan from the Collection Hermann Gerlinger, 2017-2022).

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Erträumte Reisen, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, November 16, 2018 - March 3, 2019, cat. no. 7, p. 36 (with illu. on plate 7).

LITERATURE: From the estate of Donald E. Gordon, University of Pittsburgh, Gordon Papers, series I., subseries 1, box 1, folder 140.

Donald E. Gordon, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Mit einem kritischen Katalog sämtlicher Gemälde, Munich/Cambridge 1968, p. 69 and 294, cat. no. 139 and 139 v (with illu. on p. 294 and p. 430).

Documentation of the 1958 exhibition, Archive Museum Folkwang, Essen, MF00084, l. 1f.; MF00085b, l. 1-4.

Ein Leben mit der Kunst, Wilhelm Grosshennig, Chemnitz 1921-1930, Düsseldorf 1951-1983 and 1986 (with color illu.).

Wolfgang Wittrock Kunsthandel, Gemälde, Aquarelle, Zeichnungen, Graphik. Künstler der Brücke und weitere Neuerwerbungen (catalog Wolfgang-Wittrock-Kunsthandel, no. 8), Düsseldorf 1988 (with illu.

Heinz Spielmann (ed.), Die Maler der Brücke. Sammlung Hermann Gerlinger, Stuttgart 1995, p. 259, p. 150, SHG no. 145 (with illu. on p. 151).

Michael Stitz, Interview mit Hermann Gerlinger, in: Vernissage. Die Zeitschrift zur Ausstellung, no. 4, 1995, pp. 22-25 (with illu. on p. 25).

Antje Wendt, Kunst geniessen. Reise zu Gemäldesammlungen in Schleswig-Holstein, 1999, pp. 62-69 (with illu.).

David Rosenberg, Art Game Boo. Histoire des arts du XXe Siècle, Paris 2003 (with illu.).

Heinz Spielmann, Die Brücke und die Moderne 1904-1914, in: Vernissage Nord, Ausstellungen Herbst/Winter, 2004/05, pp. 4-11 (with illu.).

Gerhard Presler, Die große Dresdner Kunstrevolte, in: Art, no. 4, 2005, pp. 26-40 (with illu.).

Hermann Gerlinger, Katja Schneider (eds.), Die Maler der Brücke. Inventory catalog Collection Hermann Gerlinger, Halle (Saale) 2005, p. 314, SHG no. 710 (with illu.).

Oskar Matzel, Von der Elbe an die Spree, in: Meike Hoffmann, Andreas Hüneke and Tobias Teumer (eds.), Festschrift für Wolfgang Wittrock. Zum 65. Geburtstag, no. 155, Freie Universität, Berlin 2012, pp. 16-18 (with illu. on p. 272, no. 10).

Inge Herold, Ulrike Lorenz and Thorsten Sadowsky (eds.), Wolfgang Henze, Verzeichnis der doppelseitig bemalten Gemälde Ernst Ludwig Kirchners, 2015, cat. no. D21 (with illu. on p. 149).

Brückenschlag: Gerlinger – Buchheim! Museumsführer durch die "Brücke"-Sammlungen von Hermann Gerlinger und Lothar-Günther Buchheim, Bernried 2017, p. 200 (with illu. on p. 201).

Kirchner's Ingenious Rendition of the "Brücke" Artists' Favourite Model – "Fränzi"

This colorful painting represents the peak of Kirchner’s vibrant Brücke style. Painted in 1910, it depicts the child model Lina Franziska Fehrmann, who was ten years old at the time. Fränzi, as she was known, is recognizable from her pointed face, her angular limbs, and her dark hair tied by a large bow, which feature in many of Kirchner’s sketches and paintings of the girl. A contemporary drawing by Max Pechstein depicts Fränzi with the same red bow in her hair, seated in an identical position on a yellow rug with her arms encircling her legs. But whereas Pechstein shows Fränzi from behind and places her within a group of bathers on the shores of the Mortizburg ponds, Kirchner adopts a close-up view, facing his model, so that she occupies the entire visual field. Pechstein’s drawing suggests that the girl’s posture, dress, and surroundings are all rooted in observed reality. Kirchner’s brilliant invention was to transform the flesh tones of Fränzi’s body into luminous sky blue, thus heightening the impact of the orange ground by juxtaposing complementary colors that lie opposite each other on the color wheel. The vibrant complementary contrasts between Fränzi’s blue body and her orange surroundings, between the red bow in her hair and the green vegetation below her left arm, are a color equivalent for the brilliant sunshine illuminating the scene.

The Dream of Merging Art and Life at the Moritzburg Ponds Near Dresden

The summer of 1910, which Kirchner, Pechstein and Erich Heckel spent in Moritzburg, north-west of Dresden, has assumed a mythical status in the history of "die Brücke". Painting and sketching, bathing nude alongside their models, playing with boomerangs and bows and arrows, and frolicking in the reeds surrounding the ponds, the artists lived their dream of merging art and life. Fired by their enthusiasm for tribal art, including carved and painted beams from the Micronesian island of Palau in the Dresden ethnographical museum, and native villages they saw on display in the zoo (which were intended to garner popular support for Germany’s colonial ambitions), they replicated what they understood as a native lifestyle. Like many of the broadly based reform movements of the early twentieth century (including nudism, sun worship, vegetarianism, and free, expressive dance), the Brücke artists aimed to renew art and society by stripping away the veneer of urban civilization and plunging back into nature.

"Don’t copy nature too closely: art is an abstraction". The Influence of French Post-Impressionism on Kirchner's Work

Kirchner pursued authenticity and spontaneity in both his subjects and his style. He experimented with angular, jagged contours, inspired by the carved beams from Palau. French Post-Impressionism was another source of inspiration: paintings by Matisse, Cézanne, and Gauguin, which Kirchner saw exhibited in Germany, together with Paul Signac’s theories concerning juxtapositions of pure complementary colors, all played an important role. Kirchner’s choice of sky blue for Fränzi’s body echoes the spirit of Gauguin’s famous advice to the painter Emil Shuffenecker: “Don’t copy nature too closely: art is an abstraction – derive this abstraction from nature by dreaming before it and think more of the creation than the result..” (Paul Gauguin, letter to Emile Schuffenecker from Pont Aven, 14.8.1888: "Un conseil, ne copiez pas trop d'après nature, l'art est une abstraction, tirez-la de la nature en rêvant devant, et pensez plus à la création qu'au résultat…", in: Maurice Malingues, Lettres de Gauguin, 1946, no. 67, p. 134).

Bright Colors, Contrasting Lines and Maximum Luminosity

Kirchner’s paintings of this period occupy a dynamic middle ground between painting and drawing. Bright colors are offset by dark, contrasting lines, such as those outlining Fränzi’s body, so that the finished work retains the immediacy, freshness, and openness of a sketch. Visible areas of primed white canvas intensify the luminous colors and play a positive role in the final image: in this instance, the girl’s petticoat is an area of primed white ground. The artist’s experiments with quick-drying oil paints thinned with benzine allowed him to work as rapidly in oil as he sketched in crayon and watercolor; by adding the “secret ingredient” of wax to his oils, which backscatters light, Kirchner was able to achieve maximum luminosity (Kirchner wrote about his “Geheimnis,” referring to his technique of adding wax to his paints, in a letter to Botho Graef, September 21, 1916).

The Freedom and Authenticity of Youth: Fränzi as a Symbol of Renewal and Regeneration

In comparison to Pechstein’s depiction of Fränzi in a group of bathers, Kirchner strips away narrative detail to focus on the ‘abstract’ qualities of his painting, building his composition around contrasting colors. Nevertheless, his subject remains important. Child and adolescent models played a vital role because youth was associated with freedom and authenticity. Magnified to occupy the entire canvas in "Das blaue Mädchen", the child assumes an idol-like presence, much as she does in Kirchner’s contemporary painting "Fränzi vor geschnitztem Stuhl" (1910). Given the sexualized content of several sketches and comments by Kirchner, controversy surrounds the exact nature of his relationship with the child (see, for example, Gerd Presler, E. L. Kirchner. Seine Frauen, seine Modelle, seine Bilder, 1998, p. 37f.). His idol-like depictions of her reflect his fascination; but they also relate to a widespread re-evaluation and elevation of childhood in the early twentieth century, which the Swedish feminist philosopher Ellen Key described as “the century of the child.” (see Ellen Key, Barnets århundrade (1900), translated into English as The Century of the Child, 1909). In Friedrich Nietzsche’s "Also sprach Zarathustra" – a known source of inspiration for die Brücke – the child is described as “innocence and forgetting, a new beginning, a game, a self-rolling wheel, a first movement, a sacred Yes.” (Friedrich Nietzsche, ‘The Three Metamorphoses’, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by R. J. Hollingdale, Penguin Classics, 1974). In keeping with Kirchner’s wider ambitions for his Moritzburg works, he undoubtedly regarded Fränzi as a symbol of renewal and regeneration.

The Verso of the Painting: The Ideal of Female Beauty and a Glimpse of Kirchner's Early Sculptures

The verso of the painting, "Gelbgrüner weibliche Halbakt" (fig.), is dated 1910/1926 in Donald Gordon’s catalogue raisonné (see Donald E. Gordon, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1968, p. 422, 139v. Areas of visible overpainting in the arms, together with the solid colors and overall opaque application of paint suggest that the verso of the canvas was reworked by Kirchner in the nineteen-twenties, when he frequently repainted earlier works to ‘update’ their style). The model for the nude may well be Kirchner’s girlfriend Doris Große (nicknamed Dodo), who represented an ideal of female beauty for Kirchner in his Dresden years. The nude is unusually confrontational, clasping her arms behind her body and thrusting her breasts forwards as she stares boldly at the artist/viewer. On the shelf behind the girl, we find objects associated with Kirchner’s early sculptures, and props that appear in his still-life paintings (a rounded jug, for example, reappears in "Stilleben mit Krug und afrikanischer Schale", 1912 (Gordon 232), and a similar lidded jug features in an early photograph of Kirchner’s studio: "The Artists Milly and Sam in Kirchner’s Studio", Berliner Strasse 80, Dresden, c.1910/11, glass negative, 13 x 18 cm, Kirchner Museum Davos). Although it is not identical with any surviving work, the small panel roughly depicting a couple above the nude’s right-hand shoulder, relates to a series of panels in clay and metal depicting lovers, which Wolfgang Henze dates 1909-1910 in his catalogue raisonné of Kirchner’s sculptures (Wolfgang Henze, Die Plastik Ernst Ludwig Kirchners, Monografie mit Werkverzeichnis, 2002).

Jill Lloyd

"Kirchner made the semi-nude on the verso around 1920, when Erna sent him his paintings from the Berlin studio to Davos without stretchers. In 1926 he reworked the painting. Thus the 'blue girl' remained in the untouched state of 1910."

Dr Wolfgang Henze

This colorful painting represents the peak of Kirchner’s vibrant Brücke style. Painted in 1910, it depicts the child model Lina Franziska Fehrmann, who was ten years old at the time. Fränzi, as she was known, is recognizable from her pointed face, her angular limbs, and her dark hair tied by a large bow, which feature in many of Kirchner’s sketches and paintings of the girl. A contemporary drawing by Max Pechstein depicts Fränzi with the same red bow in her hair, seated in an identical position on a yellow rug with her arms encircling her legs. But whereas Pechstein shows Fränzi from behind and places her within a group of bathers on the shores of the Mortizburg ponds, Kirchner adopts a close-up view, facing his model, so that she occupies the entire visual field. Pechstein’s drawing suggests that the girl’s posture, dress, and surroundings are all rooted in observed reality. Kirchner’s brilliant invention was to transform the flesh tones of Fränzi’s body into luminous sky blue, thus heightening the impact of the orange ground by juxtaposing complementary colors that lie opposite each other on the color wheel. The vibrant complementary contrasts between Fränzi’s blue body and her orange surroundings, between the red bow in her hair and the green vegetation below her left arm, are a color equivalent for the brilliant sunshine illuminating the scene.

The Dream of Merging Art and Life at the Moritzburg Ponds Near Dresden

The summer of 1910, which Kirchner, Pechstein and Erich Heckel spent in Moritzburg, north-west of Dresden, has assumed a mythical status in the history of "die Brücke". Painting and sketching, bathing nude alongside their models, playing with boomerangs and bows and arrows, and frolicking in the reeds surrounding the ponds, the artists lived their dream of merging art and life. Fired by their enthusiasm for tribal art, including carved and painted beams from the Micronesian island of Palau in the Dresden ethnographical museum, and native villages they saw on display in the zoo (which were intended to garner popular support for Germany’s colonial ambitions), they replicated what they understood as a native lifestyle. Like many of the broadly based reform movements of the early twentieth century (including nudism, sun worship, vegetarianism, and free, expressive dance), the Brücke artists aimed to renew art and society by stripping away the veneer of urban civilization and plunging back into nature.

"Don’t copy nature too closely: art is an abstraction". The Influence of French Post-Impressionism on Kirchner's Work

Kirchner pursued authenticity and spontaneity in both his subjects and his style. He experimented with angular, jagged contours, inspired by the carved beams from Palau. French Post-Impressionism was another source of inspiration: paintings by Matisse, Cézanne, and Gauguin, which Kirchner saw exhibited in Germany, together with Paul Signac’s theories concerning juxtapositions of pure complementary colors, all played an important role. Kirchner’s choice of sky blue for Fränzi’s body echoes the spirit of Gauguin’s famous advice to the painter Emil Shuffenecker: “Don’t copy nature too closely: art is an abstraction – derive this abstraction from nature by dreaming before it and think more of the creation than the result..” (Paul Gauguin, letter to Emile Schuffenecker from Pont Aven, 14.8.1888: "Un conseil, ne copiez pas trop d'après nature, l'art est une abstraction, tirez-la de la nature en rêvant devant, et pensez plus à la création qu'au résultat…", in: Maurice Malingues, Lettres de Gauguin, 1946, no. 67, p. 134).

Bright Colors, Contrasting Lines and Maximum Luminosity

Kirchner’s paintings of this period occupy a dynamic middle ground between painting and drawing. Bright colors are offset by dark, contrasting lines, such as those outlining Fränzi’s body, so that the finished work retains the immediacy, freshness, and openness of a sketch. Visible areas of primed white canvas intensify the luminous colors and play a positive role in the final image: in this instance, the girl’s petticoat is an area of primed white ground. The artist’s experiments with quick-drying oil paints thinned with benzine allowed him to work as rapidly in oil as he sketched in crayon and watercolor; by adding the “secret ingredient” of wax to his oils, which backscatters light, Kirchner was able to achieve maximum luminosity (Kirchner wrote about his “Geheimnis,” referring to his technique of adding wax to his paints, in a letter to Botho Graef, September 21, 1916).

The Freedom and Authenticity of Youth: Fränzi as a Symbol of Renewal and Regeneration

In comparison to Pechstein’s depiction of Fränzi in a group of bathers, Kirchner strips away narrative detail to focus on the ‘abstract’ qualities of his painting, building his composition around contrasting colors. Nevertheless, his subject remains important. Child and adolescent models played a vital role because youth was associated with freedom and authenticity. Magnified to occupy the entire canvas in "Das blaue Mädchen", the child assumes an idol-like presence, much as she does in Kirchner’s contemporary painting "Fränzi vor geschnitztem Stuhl" (1910). Given the sexualized content of several sketches and comments by Kirchner, controversy surrounds the exact nature of his relationship with the child (see, for example, Gerd Presler, E. L. Kirchner. Seine Frauen, seine Modelle, seine Bilder, 1998, p. 37f.). His idol-like depictions of her reflect his fascination; but they also relate to a widespread re-evaluation and elevation of childhood in the early twentieth century, which the Swedish feminist philosopher Ellen Key described as “the century of the child.” (see Ellen Key, Barnets århundrade (1900), translated into English as The Century of the Child, 1909). In Friedrich Nietzsche’s "Also sprach Zarathustra" – a known source of inspiration for die Brücke – the child is described as “innocence and forgetting, a new beginning, a game, a self-rolling wheel, a first movement, a sacred Yes.” (Friedrich Nietzsche, ‘The Three Metamorphoses’, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by R. J. Hollingdale, Penguin Classics, 1974). In keeping with Kirchner’s wider ambitions for his Moritzburg works, he undoubtedly regarded Fränzi as a symbol of renewal and regeneration.

The Verso of the Painting: The Ideal of Female Beauty and a Glimpse of Kirchner's Early Sculptures

The verso of the painting, "Gelbgrüner weibliche Halbakt" (fig.), is dated 1910/1926 in Donald Gordon’s catalogue raisonné (see Donald E. Gordon, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1968, p. 422, 139v. Areas of visible overpainting in the arms, together with the solid colors and overall opaque application of paint suggest that the verso of the canvas was reworked by Kirchner in the nineteen-twenties, when he frequently repainted earlier works to ‘update’ their style). The model for the nude may well be Kirchner’s girlfriend Doris Große (nicknamed Dodo), who represented an ideal of female beauty for Kirchner in his Dresden years. The nude is unusually confrontational, clasping her arms behind her body and thrusting her breasts forwards as she stares boldly at the artist/viewer. On the shelf behind the girl, we find objects associated with Kirchner’s early sculptures, and props that appear in his still-life paintings (a rounded jug, for example, reappears in "Stilleben mit Krug und afrikanischer Schale", 1912 (Gordon 232), and a similar lidded jug features in an early photograph of Kirchner’s studio: "The Artists Milly and Sam in Kirchner’s Studio", Berliner Strasse 80, Dresden, c.1910/11, glass negative, 13 x 18 cm, Kirchner Museum Davos). Although it is not identical with any surviving work, the small panel roughly depicting a couple above the nude’s right-hand shoulder, relates to a series of panels in clay and metal depicting lovers, which Wolfgang Henze dates 1909-1910 in his catalogue raisonné of Kirchner’s sculptures (Wolfgang Henze, Die Plastik Ernst Ludwig Kirchners, Monografie mit Werkverzeichnis, 2002).

Jill Lloyd

"Kirchner made the semi-nude on the verso around 1920, when Erna sent him his paintings from the Berlin studio to Davos without stretchers. In 1926 he reworked the painting. Thus the 'blue girl' remained in the untouched state of 1910."

Dr Wolfgang Henze