Video

Image du cadre

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

33

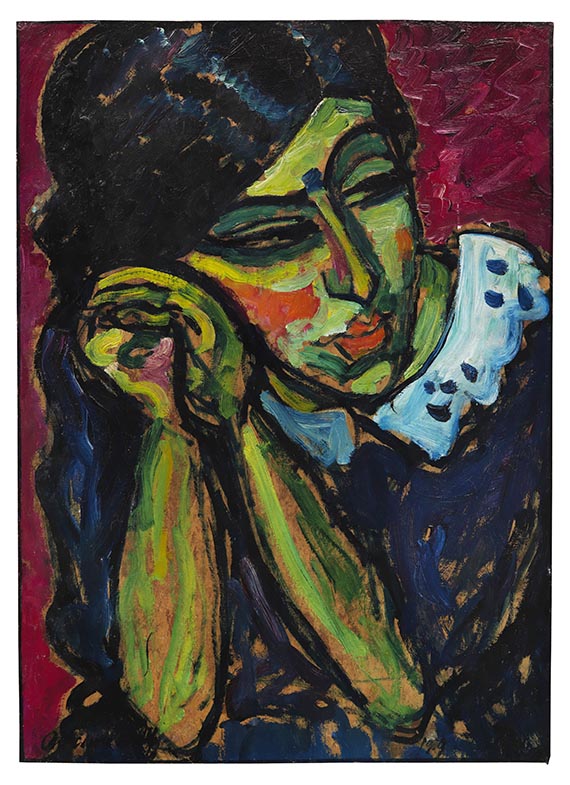

Alexej von Jawlensky

Mädchen mit Zopf, 1910.

Oil on thin cardboard, on board

Estimation:

€ 3,500,000 / $ 4,060,000 Résultat:

€ 6,383,000 / $ 7,404,279 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

Mädchen mit Zopf. 1910.

Oil on thin cardboard, on board.

Weiler 49. Jawlensky/Pieroni-Jawlensky 257. Signed in lower left and dated in lower right. 69.5 x 49.5 cm (27.3 x 19.4 in).

• "Mädchen mit Zopf“– A masterpiece of Expressionism.

• Second to none and seminal: In terms of colors and composition, a fascinating solitaire in Jawlensky's œuvre and pivotal for his creation.

• Key work of Expressionism: "Mädchen mit Zopf“ marks the beginning of Jawlensky's expressionistic creative period.

• The human portrait head is Jawlensky's central theme, through which he attained his novel expressive style before World War I.

• Of museum quality – works of a comparable quality are extremely rare on the international auction market.

• Excellent provenance: From the collection of Clemens Weiler, Wiesbaden, Jawlensky expert and author of the first catalogue raisonné.

• Comprehensive exhibition history: Shown at, among others, the legendary Jawlensky exhibition on occasion of the artist's 100th birthday at the Museum Wiesbaden and the Lenbachhaus, Munich, in 1964.

PROVENANCE: From the artist's estate (until 1957).

Collection of Dr. Clemens Weiler, Wiesbaden (directly acquired from the above in 1957, until 1968, Roman Norbert Ketterer, Campione).

Private collection Cologne (acquired from the above, presumably in 1968 - presumably until 2007, Christie's, New York, November 6, 2007, lot 62).

Private collection Switzerland (acquired from the above in 2007).

EXHIBITION: Alexej Jawlensky, Galerie Würthle, Vienna 1922 (no cat.).

Ölbilder von Alexej von Jawlensky, Galerie Alex Vömel, Düsseldorf, October 1 - Novemer 15, 1956, cat. no. 3.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Kunsthalle Bern and Saarlandmuseum Saarbrücken, May 11 - June 16, 1957, cat. no. 15.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Kunstverein in Hamburg, October to November 1957, Kunsthalle Bremen, December 12, 1957 - January 19, 1958, cat. no. 12.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Württembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart, and Städtische Kunsthalle, Mannheim, February 2 - March 16, 1958, cat. no. 17.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Städtisches Museum, Wiesbaden, March 22 - May 31, 1964, cat. no. 8.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, July 17 - September 13, 1964, cat. no. 45.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt a. Main, September 16 - October 22, 1967, pp. 46f. cat. no. 12 (with black-and-white illu., plate 12).

Alexej von Jawlensky. Gemälde, Aquarelle, Zeichnungen und Druckgrafik, Städtische Museen Jena, September 2 - November 25, 2012, cat. no. 1/18, p. 218 (with full-page color illu., p. 88).

Alexej von Jawlensky. El paisaje del rostro, Fondación Mapfre, Madrid, February 9 - May 9, 2021, cat. no. 21, pp. 125 and 290 (with full-page color illu., p. 124).

LITERATURE: Franz Ottman, Kunstausstellungen in Wien. Winter 1921 bis Frühling 1922, in: Wiener Jahrbuch für bildende Kunst, V Jahrgang, Vienna 1922, annotation on p. 13.

Clemens Weiler, Alexej Jawlensky, Cologne 1959, cat. no. 49, p. 229 (with a black-and-white illu.).

Roman Norbert Ketterer, Campione/Switzerland, Moderne Kunst V, 1968, cat. no. 54 (with a color illu. on p. 66).

Maria Jawlensky/Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky/Angelica Jawlensky, Alexej von Jawlensky. Catalogue Raisonné of the Oil Paintings, London 1991, vol. I, p. 215, cat. no. 257 (with a black-and-white illu.).

Christie's, New York, Impressionist and Modern Art Evenig Sale, November 6, 2007, lot 62 (with a color illu.).

Alexj von Jawlensky-Archiv (ed.), Reihe Bild und Wissenschaft. Forschungsbeiträge zu Leben und Werk Alexej von Jawlenskys, vol. 3, Ascona 2009, cat. no. 257, p. 60.

"[…] This was a pivotal moment for my art. And until 1914, just before the war, I painted my strongest works, known as the 'pre-war works‘, during those years.“

Alexej von Jawlensky, Lebenserinnerungen, quoted from: Clemens Weiler. Alexej Jawlensky. Köpfe – Gesichte – Meditationen, Hanau 1970, p. 112.

"The vibrant painting "Mädchen mit Zopf“ (Girl with Braid)" was created during Jawlensky's pivotal creative period, when he and his partner Marianne von Werefkin, as well as the artist couple Gabriele Münter and Wassily Kandinsky, invented German Expressionism in Murnau between 1908 and 1910."

Dr. Roman Zieglgänsberger, May 2023, Museum Wiesbaden.

Oil on thin cardboard, on board.

Weiler 49. Jawlensky/Pieroni-Jawlensky 257. Signed in lower left and dated in lower right. 69.5 x 49.5 cm (27.3 x 19.4 in).

• "Mädchen mit Zopf“– A masterpiece of Expressionism.

• Second to none and seminal: In terms of colors and composition, a fascinating solitaire in Jawlensky's œuvre and pivotal for his creation.

• Key work of Expressionism: "Mädchen mit Zopf“ marks the beginning of Jawlensky's expressionistic creative period.

• The human portrait head is Jawlensky's central theme, through which he attained his novel expressive style before World War I.

• Of museum quality – works of a comparable quality are extremely rare on the international auction market.

• Excellent provenance: From the collection of Clemens Weiler, Wiesbaden, Jawlensky expert and author of the first catalogue raisonné.

• Comprehensive exhibition history: Shown at, among others, the legendary Jawlensky exhibition on occasion of the artist's 100th birthday at the Museum Wiesbaden and the Lenbachhaus, Munich, in 1964.

PROVENANCE: From the artist's estate (until 1957).

Collection of Dr. Clemens Weiler, Wiesbaden (directly acquired from the above in 1957, until 1968, Roman Norbert Ketterer, Campione).

Private collection Cologne (acquired from the above, presumably in 1968 - presumably until 2007, Christie's, New York, November 6, 2007, lot 62).

Private collection Switzerland (acquired from the above in 2007).

EXHIBITION: Alexej Jawlensky, Galerie Würthle, Vienna 1922 (no cat.).

Ölbilder von Alexej von Jawlensky, Galerie Alex Vömel, Düsseldorf, October 1 - Novemer 15, 1956, cat. no. 3.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Kunsthalle Bern and Saarlandmuseum Saarbrücken, May 11 - June 16, 1957, cat. no. 15.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Kunstverein in Hamburg, October to November 1957, Kunsthalle Bremen, December 12, 1957 - January 19, 1958, cat. no. 12.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Württembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart, and Städtische Kunsthalle, Mannheim, February 2 - March 16, 1958, cat. no. 17.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Städtisches Museum, Wiesbaden, March 22 - May 31, 1964, cat. no. 8.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, July 17 - September 13, 1964, cat. no. 45.

Alexej von Jawlensky, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt a. Main, September 16 - October 22, 1967, pp. 46f. cat. no. 12 (with black-and-white illu., plate 12).

Alexej von Jawlensky. Gemälde, Aquarelle, Zeichnungen und Druckgrafik, Städtische Museen Jena, September 2 - November 25, 2012, cat. no. 1/18, p. 218 (with full-page color illu., p. 88).

Alexej von Jawlensky. El paisaje del rostro, Fondación Mapfre, Madrid, February 9 - May 9, 2021, cat. no. 21, pp. 125 and 290 (with full-page color illu., p. 124).

LITERATURE: Franz Ottman, Kunstausstellungen in Wien. Winter 1921 bis Frühling 1922, in: Wiener Jahrbuch für bildende Kunst, V Jahrgang, Vienna 1922, annotation on p. 13.

Clemens Weiler, Alexej Jawlensky, Cologne 1959, cat. no. 49, p. 229 (with a black-and-white illu.).

Roman Norbert Ketterer, Campione/Switzerland, Moderne Kunst V, 1968, cat. no. 54 (with a color illu. on p. 66).

Maria Jawlensky/Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky/Angelica Jawlensky, Alexej von Jawlensky. Catalogue Raisonné of the Oil Paintings, London 1991, vol. I, p. 215, cat. no. 257 (with a black-and-white illu.).

Christie's, New York, Impressionist and Modern Art Evenig Sale, November 6, 2007, lot 62 (with a color illu.).

Alexj von Jawlensky-Archiv (ed.), Reihe Bild und Wissenschaft. Forschungsbeiträge zu Leben und Werk Alexej von Jawlenskys, vol. 3, Ascona 2009, cat. no. 257, p. 60.

"[…] This was a pivotal moment for my art. And until 1914, just before the war, I painted my strongest works, known as the 'pre-war works‘, during those years.“

Alexej von Jawlensky, Lebenserinnerungen, quoted from: Clemens Weiler. Alexej Jawlensky. Köpfe – Gesichte – Meditationen, Hanau 1970, p. 112.

"The vibrant painting "Mädchen mit Zopf“ (Girl with Braid)" was created during Jawlensky's pivotal creative period, when he and his partner Marianne von Werefkin, as well as the artist couple Gabriele Münter and Wassily Kandinsky, invented German Expressionism in Murnau between 1908 and 1910."

Dr. Roman Zieglgänsberger, May 2023, Museum Wiesbaden.

"Mädchen mit Zopf" (Girl with Braid) - A vibrant masterpiece of Expressionism

In 1910, Alexej von Jawlensky created an icon of Modernism with this painting. The composition of "Mädchen mit Zopf" is as unusual as it is outstanding: the artist combines the frenetic spontaneity of the color application with the free play of form and color in a singular key work of Expressionism! Through the mysterious stylization of the female head, and a multicolor face fully emancipated from any natural model, with "Mädchen mit Zopf" Jawlensky was far ahead of the "strong and powerful heads" (Clemens Weiler) he painted in 1912. Jawlensky was at the peak of his creativity and took a step in these crucial years between 1908 and 1910 that was seminal for both his own œuvre and for modern art.

Jawlensky lets his perception, his enthusiasm for everything new flow into this portrait in an extremely free, creative and unique rendition: "Mädchen mit Zopf" is a one-of-a-kind work that marks the beginning of the artistic journey to the "colorful heads" from around 1911/12. "Mädchen mit Zopf" is steeped in the impression of nature and the experience of art. The portrait appears like a synthesis of the immediate presence of the model and a formal spiritual exercise that draws on both experiences with the works of other artists as well as on memories of one's own. Jawlensky's painting thus reflects the state of the art of his time, it incorporates latest societal trends in order to create something very unique and very special: a profound masterpiece.

The skin of the exotic "Mädchen mit Zopf" is bright green, accentuated with a strong blue, dark green, turquoise and pink-orange. The paint was applied in strong strokes onto the unprimed ground, which the artist boldly left blank here and there. In addition to the face with the large, almond-shaped eyes, Jawlensky also confidently used the elongated surfaces of the propped forearms all the way to the hands for his play of colors, which he entirely liberated from nature’s specifications. This expressive spectacle is framed by the deep black hair and the vibrant dark blue dress in front of the blazing crimson background rendered in equally lively strokes. The white and blue accentuated lace collar encloses the face, which shines in expressive color contrasts, like a bright semicircle that makes for a strong counterpoint to the exotic appeal of her deep black hair. This extraordinary color scheme in combination with the compositional mastery and spontaneity, the fascinating perspective and the close-up image section make "Mädchen mit Zopf" so special.

While Wassily Kandinsky sought the maximum liberation of color in the landscape, the young Franz Marc turned to an enraptured animal world and finally painted his first blue horses in 1911, Jawlensky entirely focused on painting portraits in the years before WW I. While during Jawlensky's early impressionistic period landscapes, still lifes and portraits were created in equal distribution, this pivotal phase was characterized by a radical concentration on the portrait. Between 1909 and 1912, Jawlensky attained the work group of the extremely colorful, largely de-individualized and sensually enraptured "Heads".

Roman Zieglgänsberger on Jawlensky's "Mädchen mit Zopf":

"The vibrant painting "Mädchen mit Zopf" was created during Jawlensky's pivotal creative period, when he and his partner Marianne von Werefkin, as well as the artist couple Gabriele Münter and Wassily Kandinsky, invented German Expressionism in Murnau between 1908 and 1910. In retrospect, both Kandinsky and Münter confirmed that Jawlensky was eminent for their art at a time shortly before the founding of the "Blauer Reiter". Only rare works like the "Mädchen mit Zopf" could have had an impact so strong that it carried others away, works that not only show Jawlensky at the peak of his painterly fervor, but that also testify to his flair for delicate color combinations. It is always amazing to see how the artist managed to settle deliberately created dissonances, such as the iridescent light blue of the collar and the dark red of the background through the adjacent green facial tones and the almost cohesive, yet very lively black of the hair, so that the effect it has on the observer is best described as an "extroverted" harmony. As a result, the painting is never boring - whenever you look at it, you get immediately involved, become a part of the picture right away. The fact that Jawlensky does not only activate emotionality through color and brushwork, but that his pictures are also of great substance, is often ignored. As biting and yet harmonious as the artist’s color scheme may be, a closer inspection reveals that his motif conception is also conflicting: the girl with the narrow eyes and the pensive look with her head resting on her hands appears calm and introverted. This clearly indicates that she is far removed from her surroundings. At the same time, however, the deep, heart-colored, almost pulsating red she is completely surrounded by, as well as the red on her cheek and the overall offensive coloring suggests that she is "seething" on the inside. This impression is supported by her restrained, swaying posture, while her arms are bend to the left, her head and gaze turn to the right. In this powerfully emotional and at the same time exceptionally subtle painting, form and content come together in an almost ideal way, something very rare and only accomplished by the greatest of modern art."

Roman Zieglgänsberger

Modern Art Curator, Museum Wiesbaden

From Impressionism and Fauvism to Expressionism - "Mädchen mit Zopf": A key work from Jawlensky's best creative period

During these crucial years, Jawlensky took a step seminal for both his own œuvre and for the development of modern art - he entirely liberated the expressive color from nature’s specifications and staged it within the reduced formal framework of an engrossed stylization and de-individualization of the human face. These important creations emanate an enigmatic aura that still fascinates us today. His most important, Fauvist-inspired portraits, such as the famous "Portrait of the Dancer Alexander Saccharoff" (1909, Lenbachhaus Munich), "Helene with a Colored Turban" (1910, Guggenheim Museum, New York), "Nikita" ( 1910, Museum Wiesbaden) or "Schokko with Red Hat" (1909, Columbus Museum of Modern Art, Ohio), are far more restrained in terms of their flesh tint and thus even more realistic. In these works it is less the face but more clothing, headgear and background where Jawlensky acted out the tremendous color forces of these years. His art-historically most important works, however, are the mysterious, at times exotically stylized female heads, in which he attained an incomparable expressionistic color scheme, especially in the multicolored portraits that are fully emancipated from any natural model. "Barbarenfürstin" (Barbarian Princess, around 1912, Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum, Hagen), "Federhut" (Plumed Hat, around 1912, Norton Simon Museum, The Galka Scheyer Collection, Pasadena) or "Spanierin" (Spanish Woman, 1913, Lenbachhaus Munich) are among the works in which Jawlensky was no longer concerned with the portrait depiction, but rather with the expression of a spiritual-emotional sensation through color and form in the spirit of the art theory of the "Blauer Reiter" and its institutional predecessor, the "Neue Künstlervereinigung München" (New Artists' Association Munich) founded in 1909. Along with Wassily Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter and Marianne von Werefkin, Jawlensky was one of the founding members of the "New Artists' Association", which expressed its artistic intentions in the 1909 manifesto written by Kandinsky: "We would like to draw your attention to an association that came into being in January 1909 [...] We act on the assumption that an artist, in addition to the impressions he receives from the outer world, from nature, constantly gathers experience from an inner world; and the quest for artistic forms that express the mutual perfusion of all these experiences - a quest for forms liberated from everything ancillary in order to attain a powerful expression of the essence - in short, the pursuit of artistic synthesis [...] ]" (quoted from: Annegret Hoberg/Helmut Friedel, Der Blaue Reiter und das Neue Bild, Munich/London/New York 1999, p. 30).

Our mysteriously musing "Mädchen mit Zopf", created in eccentrically liberated colors in 1910, is almost programmatic for this important step towards a formal simplification, an expressive empathy and a painterly overcoming of the representational motif. With the free play of the bright green flesh tone, its fancy effect increased by the yellow or modulated into a calmer-looking dark green around the mystic yes, and the bold accentuation in orange, blue and violet, Jawlensky left nature behind him and allows an insight into his inner world, his emotional sensation. Jawlensky, a bon vivant in every respect, who lived in a lengthy and fateful ménage-à-trois with Marianne von Werefkin and her young housekeeper Helene Nesnakomoff, who gave birth to their son Andreas in 1902 at the age of only 16, made the painting "Mädchen mit Zopf" an iconic stylization of female beauty and erotic appeal.

"Mädchen mit Zopf" = Helene? - A boisterous statement of sensual female beauty

"Mädchen mit Zopf" is deeply imbued with the emotional turbulence of a painter with a soft spot for the ladies, even if displayed as high-necked as in the present work. The illegitimate son Andreas spent the summer of 1909 with his parents and Marianne von Werefkin in Murnau. Jawlensky and Werefkin painted together with Kandinsky and Münter in spring and summer and were engaged in a lively artistic exchange. It was as early as on his trip to France in 1906 that Jawlensky became acquainted with the paintings of Henri Matisse and Paul Gauguin. It is the French models that Jawlensky brought back with him to Murnau where they would henceforth have a decisive impact on the common style of the artistic companions. Together they pursued a path towards a stronger autonomy of the colors and a more summary surface conception. Color was liberated in Murnau, a seminal step for German Expressionism and ultimately also for the art of the "Blauer Reiter". The close artistic exchange of these years was extremely fruitful, and Werefkin's famous salon on Giselastraße in Schwabing, a meeting place highly popular among progressive artists and bohemians, played a major role in this context, too.

While the somewhat older, highly educated and influential artist Marianne von Werefkin, with whom Jawlensky had been living since he had moved to Munich in 1896, primarily served as his intellectual partner, his young lover Helene, whom he would eventually marry in 1922 after separating from Werefkin, offered him emotional stimulus in those years. He portrayed the very young Helene in the impressionist work "Helene in Spanish costume" as early as in 1901/02. She would be his preferred model from that point on, and the artist gradually abandoned pure portraiture in depictions of her until he eventually attained stylized, color-based heads such as in "Barbarenfürstin" (Barbarian Princess, around 1912, Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum Hagen). According to Tayfun Belgin, the raised left eyebrow is a telltale sign Helene used to reveal her identity as the basis for several important female heads in Jawlensky's œuvre (cf. T. Belgin, Jawlenskys Modelle. Zur Person: Helene Nesnakomoff, in: Reihe Bild und Wissenschaft. Forschungsbeiträge zu Leben und Werk Alexej von Jawlenskys, Locarno 2005, Locarno 2005, vol. 2, pp.72f.).

Is it hence possible that Helene, then in her mid twenties, inspired the much older painter to our emotionally charged color frenzy "Mädchen mit Zopf"? Does the artist make us witness to the erotic feelings that he had for his young lover Helene in the art-historically groundbreaking year 1909? We can only puzzle over the source of inspiration for this masterpiece, which is absolutely unique in Jawlensky's œuvre, as it testifies to Jawlensky's sudden overcoming of the portrait nature of works from previous years and the accomplishment of a maximum spiritual and emotional permeation of the motif. What else is fascinating is the dissonance between the decorous lace collar and the sensual depiction of the head. But it is precisely this enigmatic, enraptured aura that makes Jawlensky's masterpiece "Mädchen mit Zopf" so unmistakable.

Dawn of Modernism

In December 1909, the famous first exhibition of the "New Munich Artists’ Association" finally took place at Galerie Thannhauser. As the works on display by, among others, Jawlensky, Kandinsky, Werefkin and Münter, were so far from accounts of reality, the exhibition received severely negative press reviews. Fritz von Ostini, for example, wrote in the December 9, 1909 issue of the "Münchener Neueste Nachrichten": "[...] As the founding manifesto of the 'New Artists' Association' explains, 'the pursuit of artistic synthesis' is revealed in the color orgies, in the detachment from nature, from truthfulness and from skills. Holy shit [...]" (quoted from: Annegret Hoberg/Helmut Friedel, Der Blaue Reiter und das Neue Bild, Munich/London/New York 1999, p. 33).

The press fought fiercely against this new form of painting, which had gone wild in the truest sense of the word, the public scolded and threatened the artists and spat on the pictures. In 1909, the art of Jawlensky and his companions was far too much for the taste of the time and the aesthetic sensibilities of their contemporaries. Today, on the other hand, the progressive artistic paths that were detached from all conventions and which they courageously pursued against all external resistance, are considered one of the most important chapters that 20th century art history has to offer. [JS/MvL]

In 1910, Alexej von Jawlensky created an icon of Modernism with this painting. The composition of "Mädchen mit Zopf" is as unusual as it is outstanding: the artist combines the frenetic spontaneity of the color application with the free play of form and color in a singular key work of Expressionism! Through the mysterious stylization of the female head, and a multicolor face fully emancipated from any natural model, with "Mädchen mit Zopf" Jawlensky was far ahead of the "strong and powerful heads" (Clemens Weiler) he painted in 1912. Jawlensky was at the peak of his creativity and took a step in these crucial years between 1908 and 1910 that was seminal for both his own œuvre and for modern art.

Jawlensky lets his perception, his enthusiasm for everything new flow into this portrait in an extremely free, creative and unique rendition: "Mädchen mit Zopf" is a one-of-a-kind work that marks the beginning of the artistic journey to the "colorful heads" from around 1911/12. "Mädchen mit Zopf" is steeped in the impression of nature and the experience of art. The portrait appears like a synthesis of the immediate presence of the model and a formal spiritual exercise that draws on both experiences with the works of other artists as well as on memories of one's own. Jawlensky's painting thus reflects the state of the art of his time, it incorporates latest societal trends in order to create something very unique and very special: a profound masterpiece.

The skin of the exotic "Mädchen mit Zopf" is bright green, accentuated with a strong blue, dark green, turquoise and pink-orange. The paint was applied in strong strokes onto the unprimed ground, which the artist boldly left blank here and there. In addition to the face with the large, almond-shaped eyes, Jawlensky also confidently used the elongated surfaces of the propped forearms all the way to the hands for his play of colors, which he entirely liberated from nature’s specifications. This expressive spectacle is framed by the deep black hair and the vibrant dark blue dress in front of the blazing crimson background rendered in equally lively strokes. The white and blue accentuated lace collar encloses the face, which shines in expressive color contrasts, like a bright semicircle that makes for a strong counterpoint to the exotic appeal of her deep black hair. This extraordinary color scheme in combination with the compositional mastery and spontaneity, the fascinating perspective and the close-up image section make "Mädchen mit Zopf" so special.

While Wassily Kandinsky sought the maximum liberation of color in the landscape, the young Franz Marc turned to an enraptured animal world and finally painted his first blue horses in 1911, Jawlensky entirely focused on painting portraits in the years before WW I. While during Jawlensky's early impressionistic period landscapes, still lifes and portraits were created in equal distribution, this pivotal phase was characterized by a radical concentration on the portrait. Between 1909 and 1912, Jawlensky attained the work group of the extremely colorful, largely de-individualized and sensually enraptured "Heads".

Roman Zieglgänsberger on Jawlensky's "Mädchen mit Zopf":

"The vibrant painting "Mädchen mit Zopf" was created during Jawlensky's pivotal creative period, when he and his partner Marianne von Werefkin, as well as the artist couple Gabriele Münter and Wassily Kandinsky, invented German Expressionism in Murnau between 1908 and 1910. In retrospect, both Kandinsky and Münter confirmed that Jawlensky was eminent for their art at a time shortly before the founding of the "Blauer Reiter". Only rare works like the "Mädchen mit Zopf" could have had an impact so strong that it carried others away, works that not only show Jawlensky at the peak of his painterly fervor, but that also testify to his flair for delicate color combinations. It is always amazing to see how the artist managed to settle deliberately created dissonances, such as the iridescent light blue of the collar and the dark red of the background through the adjacent green facial tones and the almost cohesive, yet very lively black of the hair, so that the effect it has on the observer is best described as an "extroverted" harmony. As a result, the painting is never boring - whenever you look at it, you get immediately involved, become a part of the picture right away. The fact that Jawlensky does not only activate emotionality through color and brushwork, but that his pictures are also of great substance, is often ignored. As biting and yet harmonious as the artist’s color scheme may be, a closer inspection reveals that his motif conception is also conflicting: the girl with the narrow eyes and the pensive look with her head resting on her hands appears calm and introverted. This clearly indicates that she is far removed from her surroundings. At the same time, however, the deep, heart-colored, almost pulsating red she is completely surrounded by, as well as the red on her cheek and the overall offensive coloring suggests that she is "seething" on the inside. This impression is supported by her restrained, swaying posture, while her arms are bend to the left, her head and gaze turn to the right. In this powerfully emotional and at the same time exceptionally subtle painting, form and content come together in an almost ideal way, something very rare and only accomplished by the greatest of modern art."

Roman Zieglgänsberger

Modern Art Curator, Museum Wiesbaden

From Impressionism and Fauvism to Expressionism - "Mädchen mit Zopf": A key work from Jawlensky's best creative period

During these crucial years, Jawlensky took a step seminal for both his own œuvre and for the development of modern art - he entirely liberated the expressive color from nature’s specifications and staged it within the reduced formal framework of an engrossed stylization and de-individualization of the human face. These important creations emanate an enigmatic aura that still fascinates us today. His most important, Fauvist-inspired portraits, such as the famous "Portrait of the Dancer Alexander Saccharoff" (1909, Lenbachhaus Munich), "Helene with a Colored Turban" (1910, Guggenheim Museum, New York), "Nikita" ( 1910, Museum Wiesbaden) or "Schokko with Red Hat" (1909, Columbus Museum of Modern Art, Ohio), are far more restrained in terms of their flesh tint and thus even more realistic. In these works it is less the face but more clothing, headgear and background where Jawlensky acted out the tremendous color forces of these years. His art-historically most important works, however, are the mysterious, at times exotically stylized female heads, in which he attained an incomparable expressionistic color scheme, especially in the multicolored portraits that are fully emancipated from any natural model. "Barbarenfürstin" (Barbarian Princess, around 1912, Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum, Hagen), "Federhut" (Plumed Hat, around 1912, Norton Simon Museum, The Galka Scheyer Collection, Pasadena) or "Spanierin" (Spanish Woman, 1913, Lenbachhaus Munich) are among the works in which Jawlensky was no longer concerned with the portrait depiction, but rather with the expression of a spiritual-emotional sensation through color and form in the spirit of the art theory of the "Blauer Reiter" and its institutional predecessor, the "Neue Künstlervereinigung München" (New Artists' Association Munich) founded in 1909. Along with Wassily Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter and Marianne von Werefkin, Jawlensky was one of the founding members of the "New Artists' Association", which expressed its artistic intentions in the 1909 manifesto written by Kandinsky: "We would like to draw your attention to an association that came into being in January 1909 [...] We act on the assumption that an artist, in addition to the impressions he receives from the outer world, from nature, constantly gathers experience from an inner world; and the quest for artistic forms that express the mutual perfusion of all these experiences - a quest for forms liberated from everything ancillary in order to attain a powerful expression of the essence - in short, the pursuit of artistic synthesis [...] ]" (quoted from: Annegret Hoberg/Helmut Friedel, Der Blaue Reiter und das Neue Bild, Munich/London/New York 1999, p. 30).

Our mysteriously musing "Mädchen mit Zopf", created in eccentrically liberated colors in 1910, is almost programmatic for this important step towards a formal simplification, an expressive empathy and a painterly overcoming of the representational motif. With the free play of the bright green flesh tone, its fancy effect increased by the yellow or modulated into a calmer-looking dark green around the mystic yes, and the bold accentuation in orange, blue and violet, Jawlensky left nature behind him and allows an insight into his inner world, his emotional sensation. Jawlensky, a bon vivant in every respect, who lived in a lengthy and fateful ménage-à-trois with Marianne von Werefkin and her young housekeeper Helene Nesnakomoff, who gave birth to their son Andreas in 1902 at the age of only 16, made the painting "Mädchen mit Zopf" an iconic stylization of female beauty and erotic appeal.

"Mädchen mit Zopf" = Helene? - A boisterous statement of sensual female beauty

"Mädchen mit Zopf" is deeply imbued with the emotional turbulence of a painter with a soft spot for the ladies, even if displayed as high-necked as in the present work. The illegitimate son Andreas spent the summer of 1909 with his parents and Marianne von Werefkin in Murnau. Jawlensky and Werefkin painted together with Kandinsky and Münter in spring and summer and were engaged in a lively artistic exchange. It was as early as on his trip to France in 1906 that Jawlensky became acquainted with the paintings of Henri Matisse and Paul Gauguin. It is the French models that Jawlensky brought back with him to Murnau where they would henceforth have a decisive impact on the common style of the artistic companions. Together they pursued a path towards a stronger autonomy of the colors and a more summary surface conception. Color was liberated in Murnau, a seminal step for German Expressionism and ultimately also for the art of the "Blauer Reiter". The close artistic exchange of these years was extremely fruitful, and Werefkin's famous salon on Giselastraße in Schwabing, a meeting place highly popular among progressive artists and bohemians, played a major role in this context, too.

While the somewhat older, highly educated and influential artist Marianne von Werefkin, with whom Jawlensky had been living since he had moved to Munich in 1896, primarily served as his intellectual partner, his young lover Helene, whom he would eventually marry in 1922 after separating from Werefkin, offered him emotional stimulus in those years. He portrayed the very young Helene in the impressionist work "Helene in Spanish costume" as early as in 1901/02. She would be his preferred model from that point on, and the artist gradually abandoned pure portraiture in depictions of her until he eventually attained stylized, color-based heads such as in "Barbarenfürstin" (Barbarian Princess, around 1912, Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum Hagen). According to Tayfun Belgin, the raised left eyebrow is a telltale sign Helene used to reveal her identity as the basis for several important female heads in Jawlensky's œuvre (cf. T. Belgin, Jawlenskys Modelle. Zur Person: Helene Nesnakomoff, in: Reihe Bild und Wissenschaft. Forschungsbeiträge zu Leben und Werk Alexej von Jawlenskys, Locarno 2005, Locarno 2005, vol. 2, pp.72f.).

Is it hence possible that Helene, then in her mid twenties, inspired the much older painter to our emotionally charged color frenzy "Mädchen mit Zopf"? Does the artist make us witness to the erotic feelings that he had for his young lover Helene in the art-historically groundbreaking year 1909? We can only puzzle over the source of inspiration for this masterpiece, which is absolutely unique in Jawlensky's œuvre, as it testifies to Jawlensky's sudden overcoming of the portrait nature of works from previous years and the accomplishment of a maximum spiritual and emotional permeation of the motif. What else is fascinating is the dissonance between the decorous lace collar and the sensual depiction of the head. But it is precisely this enigmatic, enraptured aura that makes Jawlensky's masterpiece "Mädchen mit Zopf" so unmistakable.

Dawn of Modernism

In December 1909, the famous first exhibition of the "New Munich Artists’ Association" finally took place at Galerie Thannhauser. As the works on display by, among others, Jawlensky, Kandinsky, Werefkin and Münter, were so far from accounts of reality, the exhibition received severely negative press reviews. Fritz von Ostini, for example, wrote in the December 9, 1909 issue of the "Münchener Neueste Nachrichten": "[...] As the founding manifesto of the 'New Artists' Association' explains, 'the pursuit of artistic synthesis' is revealed in the color orgies, in the detachment from nature, from truthfulness and from skills. Holy shit [...]" (quoted from: Annegret Hoberg/Helmut Friedel, Der Blaue Reiter und das Neue Bild, Munich/London/New York 1999, p. 33).

The press fought fiercely against this new form of painting, which had gone wild in the truest sense of the word, the public scolded and threatened the artists and spat on the pictures. In 1909, the art of Jawlensky and his companions was far too much for the taste of the time and the aesthetic sensibilities of their contemporaries. Today, on the other hand, the progressive artistic paths that were detached from all conventions and which they courageously pursued against all external resistance, are considered one of the most important chapters that 20th century art history has to offer. [JS/MvL]

33

Alexej von Jawlensky

Mädchen mit Zopf, 1910.

Oil on thin cardboard, on board

Estimation:

€ 3,500,000 / $ 4,060,000 Résultat:

€ 6,383,000 / $ 7,404,279 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

Lot 33

Lot 33