Video

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

19

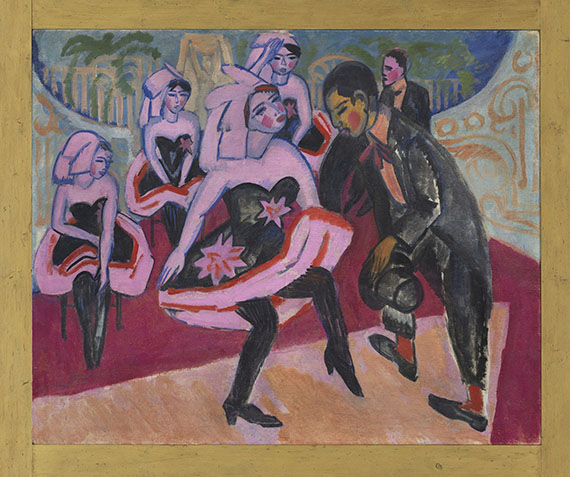

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Tanz im Varieté, 1911.

Oil on canvas

Estimation:

€ 2,000,000 / $ 2,320,000 Résultat:

€ 6,958,000 / $ 8,071,279 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

Tanz im Varieté. 1911.

Oil on canvas.

121 x 148 cm (47.6 x 58.2 in).

The work is shown in the artist's photo album I (photo 171). [CH].

• Spectacular rediscovery: hidden in a German private collection for 80 years.

• Whereabouts and colors hitherto unknown: The work was only documented by the artist's black-and-white photographs.

• Three photos show the painting in Kirchner's house "In den Lärchen" in Davos.

• Shortly after its creation, it was part of the seminal "Brücke" exhibition at Kunstsalon Fritz Gurlitt in Berlin (1912), the first and ultimately only "Brücke" group show in Berlin.

• Exceptionally large painting from the "Brücke" heyday.

• Iconic painting of a key subject in Kirchner's oeuvre: dance, circus and cabaret.

• As a pictorial account of a nightlife scene at a time of social upheaval, "Tanz im Varieté" embodies the essence of life in the modern city just as much as the famous Berlin street scenes that Kirchner created as of 1913.

The work is documented in the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern.

Export of the work from Germany will be possible.

We are grateful to Dr. Tessa Rosebrock, Kunstmuseum Basel, for her kind expert advice.

We are grateful to the heirs of Max Glaeser for the kind support in conducting the research.

PROVENANCE: Artist's studio, Davos (until at least late 1923).

Max Glaeser Collection (1871-1931), Kaiserslautern-Eselsfürth (presumably acquired from an art dealer between 1928 and 1931).

Anna Glaeser Collection, née Opp (1864-1944), Kaiserslautern-Eselsfürth (inherited from the above in 1931).

Private collection Baden-Württemberg (acquired from the above's legal estate in 1944, through the agency of Dr. Lilli Fischel and Galerie Günther Franke, Munich).

Ever since family-owned.

EXHIBITION: Brücke, Kunstsalon Fritz Gurlitt, Berlin, April 2 - 24, 1912.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Gemälde, Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer, Berlin, from

November 15, 1923 (titled "Stepptanz“).

LITERATURE: Donald E. Gordon, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Mit einem kritischen Katalog sämtlicher Gemälde, Munich/Cambridge (Mass.) 1968, no. 196 (titled "Steptanz", illu. in black and white, p. 302).

- -

Karl Scheffler, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, in: Kunst und Künstler. Illustrierte Monatsschrift für bildende Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, no. XVIII/5, issue 5, 1920, p. 219 (illustrated in black and white, p. 219).

Annemarie Dube-Heynig, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Postkarten und Briefe an Erich Heckel im Altonaer Museum in Hamburg, Cologne 1984, p. 252 (with the title “Steptanz”, illu. in b/w).

Johanna Brade, Die Zirkus- und Variétébilder der "Brücke (1905-1913): Zwischen Bildexperiment und Gesellschaftskritik. Zu Themenwahl und Motivgestaltung (PhD thesis), Berlin 1993, cat. no. 75.

Roland Scotti (ed.), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Das fotografische Werk, Wabern/Bern 2005, p. 118.

Lothar Grisebach (ed.), Ernst Ludwig Kirchners Davoser Tagebuch, Ostfildern 1997, p. 339 (photograph).

Hans Delfs (ed.), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Der Gesamte Briefwechsel ("Die absolute Wahrheit, so wie ich sie fühle"), Zürich 2010, no. 1193 and 1440 (mismatched).

Thorsten Sadowsky (ed.), ex. cat. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Der Künstler als Fotograf, Kirchner Museum Davos, November 22, 2015 - May 1, 2016, pp. 44, 66, 76, 82 and 150 (photographs).

Thorsten Sadowsky (edg.), Louis de Marsalle. Visite à Davos, Heidelberg 2018 (illustrated in black and white, p. 11, no. 2).

Thorsten Sadowsky, 'Und der Bauchtanz ging den ganzen Vormittag'. Ernst Ludwig Kirchners Davoser Tänze, in: KirchnerHAUS Aschaffenburg / Brigitte Schad (ed.), ex. cat. Kirchners Kosmos: Der Tanz, KirchnerHAUS Aschaffenburg, Munich 2018, p. 41 (titled "Stepptanz", illustrated in black and white, p. 42, no. 4).

ARCHIVE MATERIAL:

Künzig, Dr. Brunner, Dr. Koehler Attorneys at Law, Mannheim (administration of the Glaeser estate): Offer of paintings from the Max Glaeser Collection, 1931, Archive of the Kunstmuseum Basel, shelfmark F 001.024.010.000: “Varietészene”.

Galerie Buck, Mannheim: Offer of paintings by Arnold Böcklin, Lovis Corinth, Anselm Feuerbach, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Hans von Marées, Edvard Munch, Heinrich von Zügel, Max Glaeser Collection, 1932, Archive of the Kunstmuseum Basel, shelfmark F 001.025.002.000: “Variete” (sic).

Düsseldorf Municipal Archives, inventory: 0-1-4 Düsseldorf Municipal Administration from 1933-2000 (old: inventory IV), offers and purchases, sign 3769.0000, fol. 175-177.

Estate of Donald E. Gordon, University of Pittsburgh, Gordon Papers, Series 1, Subseries 1, Box 1, Folder 197.

Oil on canvas.

121 x 148 cm (47.6 x 58.2 in).

The work is shown in the artist's photo album I (photo 171). [CH].

• Spectacular rediscovery: hidden in a German private collection for 80 years.

• Whereabouts and colors hitherto unknown: The work was only documented by the artist's black-and-white photographs.

• Three photos show the painting in Kirchner's house "In den Lärchen" in Davos.

• Shortly after its creation, it was part of the seminal "Brücke" exhibition at Kunstsalon Fritz Gurlitt in Berlin (1912), the first and ultimately only "Brücke" group show in Berlin.

• Exceptionally large painting from the "Brücke" heyday.

• Iconic painting of a key subject in Kirchner's oeuvre: dance, circus and cabaret.

• As a pictorial account of a nightlife scene at a time of social upheaval, "Tanz im Varieté" embodies the essence of life in the modern city just as much as the famous Berlin street scenes that Kirchner created as of 1913.

The work is documented in the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archive, Wichtrach/Bern.

Export of the work from Germany will be possible.

We are grateful to Dr. Tessa Rosebrock, Kunstmuseum Basel, for her kind expert advice.

We are grateful to the heirs of Max Glaeser for the kind support in conducting the research.

PROVENANCE: Artist's studio, Davos (until at least late 1923).

Max Glaeser Collection (1871-1931), Kaiserslautern-Eselsfürth (presumably acquired from an art dealer between 1928 and 1931).

Anna Glaeser Collection, née Opp (1864-1944), Kaiserslautern-Eselsfürth (inherited from the above in 1931).

Private collection Baden-Württemberg (acquired from the above's legal estate in 1944, through the agency of Dr. Lilli Fischel and Galerie Günther Franke, Munich).

Ever since family-owned.

EXHIBITION: Brücke, Kunstsalon Fritz Gurlitt, Berlin, April 2 - 24, 1912.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Gemälde, Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer, Berlin, from

November 15, 1923 (titled "Stepptanz“).

LITERATURE: Donald E. Gordon, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Mit einem kritischen Katalog sämtlicher Gemälde, Munich/Cambridge (Mass.) 1968, no. 196 (titled "Steptanz", illu. in black and white, p. 302).

- -

Karl Scheffler, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, in: Kunst und Künstler. Illustrierte Monatsschrift für bildende Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, no. XVIII/5, issue 5, 1920, p. 219 (illustrated in black and white, p. 219).

Annemarie Dube-Heynig, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Postkarten und Briefe an Erich Heckel im Altonaer Museum in Hamburg, Cologne 1984, p. 252 (with the title “Steptanz”, illu. in b/w).

Johanna Brade, Die Zirkus- und Variétébilder der "Brücke (1905-1913): Zwischen Bildexperiment und Gesellschaftskritik. Zu Themenwahl und Motivgestaltung (PhD thesis), Berlin 1993, cat. no. 75.

Roland Scotti (ed.), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Das fotografische Werk, Wabern/Bern 2005, p. 118.

Lothar Grisebach (ed.), Ernst Ludwig Kirchners Davoser Tagebuch, Ostfildern 1997, p. 339 (photograph).

Hans Delfs (ed.), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Der Gesamte Briefwechsel ("Die absolute Wahrheit, so wie ich sie fühle"), Zürich 2010, no. 1193 and 1440 (mismatched).

Thorsten Sadowsky (ed.), ex. cat. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Der Künstler als Fotograf, Kirchner Museum Davos, November 22, 2015 - May 1, 2016, pp. 44, 66, 76, 82 and 150 (photographs).

Thorsten Sadowsky (edg.), Louis de Marsalle. Visite à Davos, Heidelberg 2018 (illustrated in black and white, p. 11, no. 2).

Thorsten Sadowsky, 'Und der Bauchtanz ging den ganzen Vormittag'. Ernst Ludwig Kirchners Davoser Tänze, in: KirchnerHAUS Aschaffenburg / Brigitte Schad (ed.), ex. cat. Kirchners Kosmos: Der Tanz, KirchnerHAUS Aschaffenburg, Munich 2018, p. 41 (titled "Stepptanz", illustrated in black and white, p. 42, no. 4).

ARCHIVE MATERIAL:

Künzig, Dr. Brunner, Dr. Koehler Attorneys at Law, Mannheim (administration of the Glaeser estate): Offer of paintings from the Max Glaeser Collection, 1931, Archive of the Kunstmuseum Basel, shelfmark F 001.024.010.000: “Varietészene”.

Galerie Buck, Mannheim: Offer of paintings by Arnold Böcklin, Lovis Corinth, Anselm Feuerbach, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Hans von Marées, Edvard Munch, Heinrich von Zügel, Max Glaeser Collection, 1932, Archive of the Kunstmuseum Basel, shelfmark F 001.025.002.000: “Variete” (sic).

Düsseldorf Municipal Archives, inventory: 0-1-4 Düsseldorf Municipal Administration from 1933-2000 (old: inventory IV), offers and purchases, sign 3769.0000, fol. 175-177.

Estate of Donald E. Gordon, University of Pittsburgh, Gordon Papers, Series 1, Subseries 1, Box 1, Folder 197.

If he had lived later, he probably would have painted the magic dancer Michael Jackson, too. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner loved the circus and cabaret shows, visited Gret Palucca’s and Mary Wigman’s studios and learned about Josefine Baker's "Revue Nègre" guest performance in Berlin, and was fascinated with dance, with gifted bodies and black models. He invited the circus artists Milly and Sam to his Dresden studio, where they drank, dressed up, and practiced ragtime. His notebooks are full of swift scribbles and dance poses. These ecstatic accounts of movement would sometimes inspire his paintings years later, among them paintings such as "Russische Tänzerin", "Tanzpaar" and "Totentanz der Mary Wigman" - all three of them icons of Modernism.

The painting has been considered lost for 100 years. Its reappearance is a sensation

The painting "Tanz im Varieté" is a document of the fascination that dance exerted on Kirchner. However, it had been waiting for its entrance on the stage behind the curtain of art history for almost 100 years. Kirchner made – as far as we know – three photos of the painting. The first shot documents an exhibition of the “Brücke“ painters at the Berlin gallery of Fritz Gurlitt in the spring of 1912 (fig.). The camera guides the view through a monumental portal flanked by two wooden Kirchner sculptures on the right and left side and puts full focus on the large "Tanzszene" right in the middle of the venue’s end wall. A later photograph shows a jolly scene in the "Haus in den Lärchen" in Davos (fig.). A dancing farmers couple, the painter on the left, seemingly impassive, the painting "Tanz im Varieté" behind him, unframed, negligently mounted on the wall, partially covered by a reclining chair. The photo with the self-portrait dates from 1919. The third shot was made at the request of the art critic Karl Scheffler; it was published alongside a Scheffler essay on Kirchner’s nervous, highly intuitive working method in the art magazine "Kunst und Künstler". The last time that "Tanz im Varieté" was on public display was in an exhibition at Paul Cassirer in Berlin in late 1923. Shortly after, the painting disappeared from the scene. Its reappearance is a real sensation.

Modernity was born on the stages and in the streets

What do we see in the painting? Kirchner described the latest trend in major European cities around 1900, something that would cause real hype on dance floors. In the cone of the spotlight in the foreground, we see a cakewalk scene between a black dancer and a white dancer, surrounded by a group of other performers. Kirchner fills the body contours with colored areas. A dense palette of red and pink hues dominates. The contrast between dark and light skin is highlighted. A variety show setting can be seen in the background. Pastel green ornaments on a balustrade and a row of palm trees suggest a winter garden. "Tanz im Varieté" is characterized by an opulent charm. It is an homage to the Golden Age of entertainers, who sent audiences into ecstasy with their show dances before the First World War. The painting is one of the last works on the theme of the circus and cabaret that Ernst Ludwig Kirchner made in Dresden before he put increasing focus on the theater in the streets of Berlin.

Modernity was born on the stages and in the streets. The combination of dignity and elegance, the refinement of fashion, and the precision of accelerated dance movements lent people in the first decades of the 20th century an aura of status and aloofness. Hardly anyone perceived the cosmopolitan flair and the sophisticated coldness as subtly as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. He had no use for the motionless academy nudes and sought inspiration in encounters with people instead. Concepts of physicality, gender roles, and cultures of motion were redefined on the capital's streets and squares, in its dance halls and theaters. A social and cultural revolution that Kirchner rendered in drawings and paintings. His pictures are descriptions of the present and sensitize the viewer to the imbalance of his figures in a striking manner. They express the unpromising nature of the glittering promises of happiness in a society in which the likelihood of failure becomes already evident in the dancers’ bodies.

One has to imagine theaters in the early 20th century as vibrant entertainment machines, a kind of 'total theater' for a mass society in search of unsacred miracles. The audience in the German Empire craved sensations, and show stars of international fame. In Dresden, the Central-Theater, the Flora-Varieté with its summer stage in the garden of the Hotel Hammer (fig.), and the Circus Albert Schumann were among the top venues for high-octane acrobatics, magic tricks, and glamour. Sarah Bernhardt, Harry Houdini and Eleonora Duse had shows in Dresden. Companies from India, China, and the USA performed at the dance venues. The world came to visit. The famous line from André Heller's album "Nr.1" comes to mind: "People everywhere carry a circus beneath their hearts, one with real tightrope walkers ..". For Kirchner and his painter friend Erich Heckel, the spot below their hearts must have been the size of a circus ring. Between 1908 and 1914, they drew, painted, and printed hundreds of sheets with motifs from circuses, fairgrounds, and cabarets.

The Cakewalk

One of the most popular types of dance in these years was the cakewalk, which can be traced back to slavery. Originally, it was African Americans mocking the dances of their white masters in competitions. The winning couple received a cake as a prize, hence the name: cakewalk. The dance migrated from the plantations to the stages of the Northern states, where it became popular with white people in blackface. Around the turn of the century, more and more African-American artists found their way onto the stages. They toured Europe, and with their performances of revealing ragtime rhythms in elegant evening apparel, they challenged the social dances of the bourgeois and aristocracy. The illustrated magazine "Elegante Welt" dedicated an extra "ball issue" to this trend and observed that the dances of the high society could no longer be distinguished from those of the demimonde (K. O. Ebner, Von der Quadrille zum "Turkey trot", in: Elegante Welt, 1912, issue 8, p. 16). Step-by-step instructions and dance schools democratized modern dance. Anyone could learn it, as it is a promenade dance in an open pose, individually and not following a specific pattern. A dance for everyone on both sides of the color lines.

Cultures started to blend on German dance floors, too. Southern dance was a popular import from the USA. In October 1901, the New York dance couple Dora Dean and Charles Johnson arrived in Berlin and performed on the stage of the Wintergarten Theater on Friedrichstrasse. The Lousiana Amazon Guards performed their first show in Germany at Circus Schumann in December (cf. Rainer E. Lotz, The "Lousiana Troupes" in Europe, in: The Black Perspective in Music, Autumn, 1983, vol. 11, no. 2, page 135). The barefoot dancer Mildred Howard de Grey danced the first cakewalk in an encore in Dresden in 1903 (cf. Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten, July 18, 1903). In Berlin, the frivolous performances of the danseuses and the suave chic of black figures in tailcoats and top hats became a stereotype with several second-level messages: their "real" black skin stands for a promise of authenticity, for an ecstatic, spontaneous lifestyle and a mixture of subordination and self-assertion. The polemical nature of the dance is retained as a subtext, for example when the cakewalk dancers bring the upright posture of classical dance into an oblique position accompanied by frivolous pelvic circles, wobbling knees, and feet that tap to the beat at the speed of lightning. "The cakewalk", writes historian Astrid Kusser, "marks the arrival of black culture in Europe" (Astrid Kusser, Arbeitsfreude und Tanzwut im (Post)-Fordismus, in: Body Politics 1 (2023), issue 1, p.47).

The emergence of black dances coincided with another contemporary phenomenon, the spread of amusing picture postcards and humorous advertising prints. African-American motifs circulated between Europe and the USA and became part of everyday communication, frequently with racist or sexist notions. Dance scenes were among the most popular motifs. The dancing black dandy - as Kirchner prominently depicted him in the present work - was among the prime movers of modern dance. With his self-confident claim to happiness and visibility, the forms of expression of the black diaspora became subject to renegotiation. Dance entered the 20th century through the gates these border crossers had opened.

Kirchner's Expressionism: a Patchwork of Cultures

Like the new German dance, the Expressionism of the "Brücke" painters also represented a patchwork of cultures in the shadow of a late autocratic regime. Kirchner, an extremely meticulous chronicler of his creations, documented his processes of appropriation. His archive of photographs, journals, letters, and sketchbooks provides exemplary forensic evidence allowing the provenance of every gesture, every motif, and every form to be reconstructed with a high degree of precision. (Fig. 10) A series of preliminary works, related motifs, and drawings reveal cross-references to other paintings and other artists. His close friendship with Erich Heckel in particular gives several clues as to the context, the subject, and the setting the painting was created in. Nature, body, and motion - these were the defining themes the painter friends shared during these years. When a competition for a poster was announced in the run-up to a major hygiene exhibition in Dresden in 1911, the two submitted a joint design with an archery motif. Although a different design was honored with the prize, Kirchner’s and Heckel's contribution received honorable mention (cf. Bernd Hünlich, Heckels und Kirchners verschollene Plakatentwürfe für die Internationale Hygiene-Ausstellung in Dresden 1911, in: Dresdener Kunstblätter, 1984, issue 28, pp. 145-151). Kirchner's lithograph "Cake Walk" (fig.) and the watercolor "Tanzszene (Stepptanz)" (fig.) - both can be seen as preliminary works to "Tanz im Varieté" - are so similar in form and motif to Heckel's lithograph "Tänzerinnen" (fig.) that it is safe to assume that the two painters attended the same dance event in Dresden in the summer of 1911.

It frequently becomes evident that Kirchner's paintings are colorful transformations of his shorthand-like drawings. This is particularly true of his dance motifs. It seems likely that he used second-hand images from magazines, advertising, or amusing postcards to reinforce his own visual experience to work up his sketch material for a painting. Whether this happened in Dresden or already in Berlin, where he relocated in October 1911, in the case of "Tanz im Varietéte" can no longer be determined. What is interesting in this respect is the aesthetic process.

Modernism would be inconceivable without the interplay of appropriation, citation, and collage. The intensity of Expressionist painting is closely linked to the ability to bring similar and dissimilar things together. The blended and the hybrid are part and parcel of the group's understanding of their work on the eve of World War I. The painting "Tanz im Varieté" takes us to a moment in Modernism when things began to change: Gestures, gender relations, forms of domination, the relationship to our bodies and other cultures.

A work like that of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner sensitizes us to the loop-like exchange of hitherto unknown abstract forms between Europe, Africa, and the USA, which - increasingly inseparably - started to interweave and intertwine. Kirchner's eye for kinetically super-talented characters demonstrates how new expressions in art arise from cultural encounters and exchange.

We often see people or things that have long eluded our gaze in a new and more complex way. The present work "Tanz im Varieté" once more poses the truely relevant questions: Questions about longing, beauty, respect, and living together in communities. It tells us about it in a highly contemporary way - spirited and tender.

Marietta Piekenbrock

Sketch - Drawing - Oil Painting. Three Stages on the Way to Completion

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner loved situations like this - and revisited them time and again throughout his life: people in motion, whether outdoors, by the sea, in the studio, under the circus dome, in the theater, at the cabaret, or, as is the case here, on the stage of a variety show, immersed in the whirling staccato of the tap dance and the catchy rhythms of the cakewalk. It was just a short step from what he saw and experienced to what he noted in "heilige Zeichen" (hieroglyphics). Just as it was the case with this work. A visit to a show - and there it was, that magic moment when everything adds up, when everything falls into place.

Without any hesitation, Kirchner pulled out his sketchbook and quickly filled the first sheet (in statement size) with precise lines: the dancer in a wide swinging skirt, her step aligned with that of her dance partner, who, in tails and top hat, drives the action. (Fig.)

Immediately followed by a next sheet with rounded corners and red edges: Kirchner changed his position, looking onto the stage through a couple in front of him. The dancer now shows a large flower in the lower part of her outfit as an eye-catcher. And the dancer wears a long elegant "swallowtail" that goes all the way down to the back of his knees. (Fig.)

Later that night, presumably after he had returned to the peace and quiet of his studio, the artist was still on fire: he intensified the scene's density on a larger sheet (26 x 36 cm), showing the entire company, including three more female dancers and a male dancer. (Fig.) What a marvelous coincidence that a fourth sheet with Kirchner's colorful exploration of the "tap dance" subject has also survived. (Fig.) A motif, carried out over four stages. Tracing such a processis a true and rare stroke of luck! Here, however, it happened and paved the way to the painting and its unique, above all colorful, creative potential, which Kirchner would seize - and use!

This painting must have meant a lot to him: Like a welcome message, it used to adorn the wall on the first floor of the "Lärchenhaus" (fig.) in 1919 - when his partner Erna Schilling left Berlin for good and moved in with him in Frauenkirch. Perhaps it served a reminder of their first encounter at a Berlin cabaret at the turn of the year 1911/12.

Prof. Dr. Dr. Gerd Presler

Provenance

When Donald E. Gordon published the first catalogue raisonné of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's paintings in 1968, he only had the aforementioned black-and-white photo of "Tanz im Varieté" from 1920 at his disposal. He had no idea of its impressive dimensions, nor did he know anything about other photos that showed the work - a rare fortunate incidence - "on site" in Kirchner's studio (above fig.). And its location? Unknown. " Whereabouts unknown". The work would not resurface in public until 2024. But where had it been during most of the past century? The handwritten collection inventory of the former owner provides research with the decisive clue: "acquired by Dr. Lili [sic] Fischel from the Gläser [sic] Collection, Eselsfürth Kaiserslautern in 1944".

Avant-garde in Kaiserslautern: the Max Glaeser Collection, Eselsfürth

The collection of commercial councilor Dr. Max Glaeser (fig.) is well known. As early as in 1907, the successful enamel manufacturer from the Kaiserslautern district of Eselsfürth began to amass an impressive collection of German art from the 19th and early 20th centuries, primarily from Munich. It comprised Lenbach and Stuck, Grützner and Thoma, Spitzweg and Liebermann, but initially no Expressionistm. The first collection catalog, written by the art historian Hugo Kehrer in 1922, provides a detailed evaluation (Hugo Kehrer, Sammlung Max Glaeser, Eselsfürth, Munich 1922). When the next collection catalog was published four years later, works by Corinth and Kokoschka (his cityscape "Madrid") had already been added to the collection. Modernism made its entrance (cf.: Edmund Hausen, Die Sammlung Glaeser, Eselsführt, in: Mitteilungsblatt des Pfälzischen Gewerbemuseums 1, 1926, pp. 41-46).

In 1928/29, the architect Hans Herkommer built a Bauhaus-style villa for Max Glaeser in Eselsfürth, a district of Kaiserslautern (fig.). The family residence was also intended to serve as an exhibition venue for the owner's large art collection. Photos of the premises were published in 1929/30, they show the tasteful avant-garde setting, by today's standards modern and contemporary to the last detail, the perfect environment for a presentation of the works of art (fig.). Edvard Munch and Emil Nolde, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Georg Kolbe, Karl Hofer and Max Pechstein were already among the big names in this important collection (fig., cf.: Edmund Hausen and Hermann Graf, Haus und Sammlung Gläser, in: Hand und Maschine 1, 1929, pp. 105-124, and Edmund Hausen, Die Sammlung Max Glaeser, Eselsfürth, in: Der Sammler, no. 2, January 15, 1930, pp. 25f.). And in October 1930, only months before the death of the then severely ill industrialist, Glaeser informed the art dealer Thannhauser that he wanted to sell the collection with the intention of only acquiring works by modern artists (Zentralarchiv des internationalen Kunsthandels ZADIK, Cologne, A 77, estate of Thannhauser, XIX 0063: client file Glaeser).

Kirchner and Max Glaeser

Two works by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner also became part of the Glaeser Collection around 1930/31. One of them had long been known: "Frühlingslandschaft" (Spring Landscape), today part of the collection of the Pfalzgalerie in Kaiserslautern (fig.). The second Kirchner painting in Glaeser's collection is now on public display for the first time in a century: "Tanz im Varieté".

"Tanz im Varieté" certainly entered the Glaeser Collection after 1928, and very likely only after January 1930. The collector visited the artist in Davos as early as in 1928, apparently encouraged by his advisor, the important art historian Gustav Hartlaub. Glaeser did not buy anything, and Kirchner was notably displeased with the visit (fig.). Glaeser's first acquisition of a Kirchner painting was the 70 by 90 centimeter "Frühlingslandschaft", which found mention as "Landschaft mit Blütenbäumen" (Landscape with Blossoming Trees) in the last contemporary collection catalog published in January 1930 - while "Tanz im Varieté" had not yet been included.

In 1935, four years after Glaeser's death, his widow Anna wanted to sell the collection in various places. The reason behind the urgency is unclear, but it clearly had nothing to do with Nazi dictatorship. The Protestant Glaeser family were not among those persecuted by the regime.

On the occasion of the numerous sales in 1935, Kirchner also recalled the 1928 visit. He told Hagemann that Glaeser had not purchased anything during his stay in Davos, but that he had later bought the painting "Artisten" from an art dealer, which he, Kirchner, could not identify: Glaeser "bought the painting Artists from an art dealer, not from me, and I don't know which one it is". (November 19, 1935, Kirchner to Hagemann, in: Hans Delfs (ed.), Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff, Nolde, Nay ... Briefe an den Sammler und Mäzen Carl Hagemann 1906-1940, Ostfildern 2004, Letter 642, p. 502). What he probably meant here was "Tanz im Varieté".

But why did Max Glaeser choose this particular painting, which is so special in terms of format, color scheme and choice of motif? An anecdote shared by the collector's family should at least be mentioned here: Max Glaeser, who traveled a lot for work, saw a performance by Josefine Baker in Paris. He even danced with her on stage (photographs documenting that evening are lost). Perhaps it was the memory of a special evening in Paris that was behind Max Glaeser's decision to buy "Tanz im Varieté".

In Glaeser's Estate: 1931-1944

When Max Glaeser died in May 1931, "Tanz im Varieté" was part of his legal estate. On September 29 of the same year, the administrator of his estate offered it to the public collection 'Kunstsammlung Basel' as "Varietészene". In the spring and summer of 1932, the painting was on consignment at Galerie Buck in Mannheim, and correspondence with the Basel museum has been preserved. Despite the conservator's now genuine interest in both Kirchner paintings from the Glaeser estate, which were offered with considerable prices of 2,800 Reichsmarks for "Frühlingslandschaft" and 5,500 Reichsmarks for "Tanz im Varieté", a purchase was never realized. Neither with the Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf, to whom Galerie Buck also offered the painting in 1932.

"Tanz im Varieté" remained in the possession of the widow Anna Glaeser, the last written record of it can be found in a collection inventory from February 1943. Anna Glaeser died in February 1944, almost exactly a year after this collection had been listed, and the remaining inventory - ten paintings, mainly by modern artists such as Pechstein, Schmidt-Rottluff, Feininger and Heckel, as well as two sculptures by Kolbe - was distributed among her grandchildren. "Tanz im Varieté" was on the distribution list, but was no longer assigned to an heir, instead it had got a check mark - the work was sold.

Sale and Salvage: 1944-2024

This is where the story the buyer's family tells takes over and completes the history of "Tanz im Varieté".

The new owner was a jewelry designer from Baden, born in 1905, who kept in touch with his avant-garde circle of friends as best he could during the war years. Among them was Lilli Fischel, who had been dismissed from the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe on account of her Jewish origins. She went into hiding in Munich and kept her head above water as free-lancer for Galerie Günther Franke. Lilli Fischel organized the purchase of "Tanz im Varieté" in 1944. In March 1944, she wrote to the art dealer Ferdinand Möller, presumably with reference to the same transaction: "Wouldn't you perhaps have a good painting by Kirchner for sale, like the ones I saw in your gallery in the past? A friend of mine, a keen expert, would like one" (Berlinische Galerie, Ferdinand Möller estate, BG-GFM-C,II 1,169).

It is no coincidence that Lilli Fischel finds her friend a painting from the Glaeser estate. After all, she had known the collection quite well for a long time: Max Glaeser had tried to sell the bulk of his paintings to a museum in 1930 at a point when he already was in poor health. This way the collector wanted to preserve his collection for future generations. He was also in contact with Lilli Fischel, at that time working for the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, about this. On October 20, 1930, the art dealer Thannhauser noted the following about a conversation with the collector: "Miss Fischel, from the Karlsruhe Museum, offered him 150,000 marks for it, while reserving the right to sell parts of it, as not everything was suitable for her museum. He is quite displeased with her because of this poor offer" (Zentralarchiv des internationalen Kunsthandels ZADIK, Cologne, A 77, estate Thannhauser, XIX 0063: client file Glaeser). Hence it stands to reason that Lilli Fischel, in search of a suitable Kirchner painting for her friend, contacted the heirs of the Glaeser Collection. This is how the painting ended up with the jewelry designer. From an early stage, he was enthusiastic about avant-garde art like Expressionism and Bauhaus. From 1923 to 1927, he trained at the Art Students League in New York alongside Alexander Calder, before he went on to spend a year in Paris to deepen his studies.

In 1944, however, such a purchase was not without difficulties. Where to put the monumental work by a "degenerate" artist, how to protect it from air raids and the National Socialist authorities in the midst of World War II? The painting was thought to be safe at a farm in the countryside where it was kept in a heavy duty crate. However, when French troops took the village in 1945, the crate was discovered and forced open. The canvas was damaged by a bullet and a stab with the bayonet: A bullet hit the head of one of the female dancers on the left while the the male dancer's torso was pierced. Fortunately, the soldiers, left the crate with the painting behind. In this way, a highly significant piece of German art history could was rescued. After the war, the painting was expertly restored at the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe by Verena Baier (fig.), once again with the help of Lilli Fischel. Today, the war damages are only visible on the work's reverse side and make the historic events tangible. To this day, "Tanz im Varieté" has remained in the family of the 1944 buyer. In 1980, on the occasion of his 75th birthday, the collector gave the painting to his two children. With this gift, however, he also assigned them the task of returning the painting to the public, for which the artist himself had also intended it. This special legacy from a special collector enables us to rediscover this work of art today. More than 100 years have passed since the painting was last published. Now it is back. "Tanz im Varieté" can finally take its rightful place in art history.

Dr. Agnes Thum

The painting has been considered lost for 100 years. Its reappearance is a sensation

The painting "Tanz im Varieté" is a document of the fascination that dance exerted on Kirchner. However, it had been waiting for its entrance on the stage behind the curtain of art history for almost 100 years. Kirchner made – as far as we know – three photos of the painting. The first shot documents an exhibition of the “Brücke“ painters at the Berlin gallery of Fritz Gurlitt in the spring of 1912 (fig.). The camera guides the view through a monumental portal flanked by two wooden Kirchner sculptures on the right and left side and puts full focus on the large "Tanzszene" right in the middle of the venue’s end wall. A later photograph shows a jolly scene in the "Haus in den Lärchen" in Davos (fig.). A dancing farmers couple, the painter on the left, seemingly impassive, the painting "Tanz im Varieté" behind him, unframed, negligently mounted on the wall, partially covered by a reclining chair. The photo with the self-portrait dates from 1919. The third shot was made at the request of the art critic Karl Scheffler; it was published alongside a Scheffler essay on Kirchner’s nervous, highly intuitive working method in the art magazine "Kunst und Künstler". The last time that "Tanz im Varieté" was on public display was in an exhibition at Paul Cassirer in Berlin in late 1923. Shortly after, the painting disappeared from the scene. Its reappearance is a real sensation.

Modernity was born on the stages and in the streets

What do we see in the painting? Kirchner described the latest trend in major European cities around 1900, something that would cause real hype on dance floors. In the cone of the spotlight in the foreground, we see a cakewalk scene between a black dancer and a white dancer, surrounded by a group of other performers. Kirchner fills the body contours with colored areas. A dense palette of red and pink hues dominates. The contrast between dark and light skin is highlighted. A variety show setting can be seen in the background. Pastel green ornaments on a balustrade and a row of palm trees suggest a winter garden. "Tanz im Varieté" is characterized by an opulent charm. It is an homage to the Golden Age of entertainers, who sent audiences into ecstasy with their show dances before the First World War. The painting is one of the last works on the theme of the circus and cabaret that Ernst Ludwig Kirchner made in Dresden before he put increasing focus on the theater in the streets of Berlin.

Modernity was born on the stages and in the streets. The combination of dignity and elegance, the refinement of fashion, and the precision of accelerated dance movements lent people in the first decades of the 20th century an aura of status and aloofness. Hardly anyone perceived the cosmopolitan flair and the sophisticated coldness as subtly as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. He had no use for the motionless academy nudes and sought inspiration in encounters with people instead. Concepts of physicality, gender roles, and cultures of motion were redefined on the capital's streets and squares, in its dance halls and theaters. A social and cultural revolution that Kirchner rendered in drawings and paintings. His pictures are descriptions of the present and sensitize the viewer to the imbalance of his figures in a striking manner. They express the unpromising nature of the glittering promises of happiness in a society in which the likelihood of failure becomes already evident in the dancers’ bodies.

One has to imagine theaters in the early 20th century as vibrant entertainment machines, a kind of 'total theater' for a mass society in search of unsacred miracles. The audience in the German Empire craved sensations, and show stars of international fame. In Dresden, the Central-Theater, the Flora-Varieté with its summer stage in the garden of the Hotel Hammer (fig.), and the Circus Albert Schumann were among the top venues for high-octane acrobatics, magic tricks, and glamour. Sarah Bernhardt, Harry Houdini and Eleonora Duse had shows in Dresden. Companies from India, China, and the USA performed at the dance venues. The world came to visit. The famous line from André Heller's album "Nr.1" comes to mind: "People everywhere carry a circus beneath their hearts, one with real tightrope walkers ..". For Kirchner and his painter friend Erich Heckel, the spot below their hearts must have been the size of a circus ring. Between 1908 and 1914, they drew, painted, and printed hundreds of sheets with motifs from circuses, fairgrounds, and cabarets.

The Cakewalk

One of the most popular types of dance in these years was the cakewalk, which can be traced back to slavery. Originally, it was African Americans mocking the dances of their white masters in competitions. The winning couple received a cake as a prize, hence the name: cakewalk. The dance migrated from the plantations to the stages of the Northern states, where it became popular with white people in blackface. Around the turn of the century, more and more African-American artists found their way onto the stages. They toured Europe, and with their performances of revealing ragtime rhythms in elegant evening apparel, they challenged the social dances of the bourgeois and aristocracy. The illustrated magazine "Elegante Welt" dedicated an extra "ball issue" to this trend and observed that the dances of the high society could no longer be distinguished from those of the demimonde (K. O. Ebner, Von der Quadrille zum "Turkey trot", in: Elegante Welt, 1912, issue 8, p. 16). Step-by-step instructions and dance schools democratized modern dance. Anyone could learn it, as it is a promenade dance in an open pose, individually and not following a specific pattern. A dance for everyone on both sides of the color lines.

Cultures started to blend on German dance floors, too. Southern dance was a popular import from the USA. In October 1901, the New York dance couple Dora Dean and Charles Johnson arrived in Berlin and performed on the stage of the Wintergarten Theater on Friedrichstrasse. The Lousiana Amazon Guards performed their first show in Germany at Circus Schumann in December (cf. Rainer E. Lotz, The "Lousiana Troupes" in Europe, in: The Black Perspective in Music, Autumn, 1983, vol. 11, no. 2, page 135). The barefoot dancer Mildred Howard de Grey danced the first cakewalk in an encore in Dresden in 1903 (cf. Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten, July 18, 1903). In Berlin, the frivolous performances of the danseuses and the suave chic of black figures in tailcoats and top hats became a stereotype with several second-level messages: their "real" black skin stands for a promise of authenticity, for an ecstatic, spontaneous lifestyle and a mixture of subordination and self-assertion. The polemical nature of the dance is retained as a subtext, for example when the cakewalk dancers bring the upright posture of classical dance into an oblique position accompanied by frivolous pelvic circles, wobbling knees, and feet that tap to the beat at the speed of lightning. "The cakewalk", writes historian Astrid Kusser, "marks the arrival of black culture in Europe" (Astrid Kusser, Arbeitsfreude und Tanzwut im (Post)-Fordismus, in: Body Politics 1 (2023), issue 1, p.47).

The emergence of black dances coincided with another contemporary phenomenon, the spread of amusing picture postcards and humorous advertising prints. African-American motifs circulated between Europe and the USA and became part of everyday communication, frequently with racist or sexist notions. Dance scenes were among the most popular motifs. The dancing black dandy - as Kirchner prominently depicted him in the present work - was among the prime movers of modern dance. With his self-confident claim to happiness and visibility, the forms of expression of the black diaspora became subject to renegotiation. Dance entered the 20th century through the gates these border crossers had opened.

Kirchner's Expressionism: a Patchwork of Cultures

Like the new German dance, the Expressionism of the "Brücke" painters also represented a patchwork of cultures in the shadow of a late autocratic regime. Kirchner, an extremely meticulous chronicler of his creations, documented his processes of appropriation. His archive of photographs, journals, letters, and sketchbooks provides exemplary forensic evidence allowing the provenance of every gesture, every motif, and every form to be reconstructed with a high degree of precision. (Fig. 10) A series of preliminary works, related motifs, and drawings reveal cross-references to other paintings and other artists. His close friendship with Erich Heckel in particular gives several clues as to the context, the subject, and the setting the painting was created in. Nature, body, and motion - these were the defining themes the painter friends shared during these years. When a competition for a poster was announced in the run-up to a major hygiene exhibition in Dresden in 1911, the two submitted a joint design with an archery motif. Although a different design was honored with the prize, Kirchner’s and Heckel's contribution received honorable mention (cf. Bernd Hünlich, Heckels und Kirchners verschollene Plakatentwürfe für die Internationale Hygiene-Ausstellung in Dresden 1911, in: Dresdener Kunstblätter, 1984, issue 28, pp. 145-151). Kirchner's lithograph "Cake Walk" (fig.) and the watercolor "Tanzszene (Stepptanz)" (fig.) - both can be seen as preliminary works to "Tanz im Varieté" - are so similar in form and motif to Heckel's lithograph "Tänzerinnen" (fig.) that it is safe to assume that the two painters attended the same dance event in Dresden in the summer of 1911.

It frequently becomes evident that Kirchner's paintings are colorful transformations of his shorthand-like drawings. This is particularly true of his dance motifs. It seems likely that he used second-hand images from magazines, advertising, or amusing postcards to reinforce his own visual experience to work up his sketch material for a painting. Whether this happened in Dresden or already in Berlin, where he relocated in October 1911, in the case of "Tanz im Varietéte" can no longer be determined. What is interesting in this respect is the aesthetic process.

Modernism would be inconceivable without the interplay of appropriation, citation, and collage. The intensity of Expressionist painting is closely linked to the ability to bring similar and dissimilar things together. The blended and the hybrid are part and parcel of the group's understanding of their work on the eve of World War I. The painting "Tanz im Varieté" takes us to a moment in Modernism when things began to change: Gestures, gender relations, forms of domination, the relationship to our bodies and other cultures.

A work like that of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner sensitizes us to the loop-like exchange of hitherto unknown abstract forms between Europe, Africa, and the USA, which - increasingly inseparably - started to interweave and intertwine. Kirchner's eye for kinetically super-talented characters demonstrates how new expressions in art arise from cultural encounters and exchange.

We often see people or things that have long eluded our gaze in a new and more complex way. The present work "Tanz im Varieté" once more poses the truely relevant questions: Questions about longing, beauty, respect, and living together in communities. It tells us about it in a highly contemporary way - spirited and tender.

Marietta Piekenbrock

Sketch - Drawing - Oil Painting. Three Stages on the Way to Completion

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner loved situations like this - and revisited them time and again throughout his life: people in motion, whether outdoors, by the sea, in the studio, under the circus dome, in the theater, at the cabaret, or, as is the case here, on the stage of a variety show, immersed in the whirling staccato of the tap dance and the catchy rhythms of the cakewalk. It was just a short step from what he saw and experienced to what he noted in "heilige Zeichen" (hieroglyphics). Just as it was the case with this work. A visit to a show - and there it was, that magic moment when everything adds up, when everything falls into place.

Without any hesitation, Kirchner pulled out his sketchbook and quickly filled the first sheet (in statement size) with precise lines: the dancer in a wide swinging skirt, her step aligned with that of her dance partner, who, in tails and top hat, drives the action. (Fig.)

Immediately followed by a next sheet with rounded corners and red edges: Kirchner changed his position, looking onto the stage through a couple in front of him. The dancer now shows a large flower in the lower part of her outfit as an eye-catcher. And the dancer wears a long elegant "swallowtail" that goes all the way down to the back of his knees. (Fig.)

Later that night, presumably after he had returned to the peace and quiet of his studio, the artist was still on fire: he intensified the scene's density on a larger sheet (26 x 36 cm), showing the entire company, including three more female dancers and a male dancer. (Fig.) What a marvelous coincidence that a fourth sheet with Kirchner's colorful exploration of the "tap dance" subject has also survived. (Fig.) A motif, carried out over four stages. Tracing such a processis a true and rare stroke of luck! Here, however, it happened and paved the way to the painting and its unique, above all colorful, creative potential, which Kirchner would seize - and use!

This painting must have meant a lot to him: Like a welcome message, it used to adorn the wall on the first floor of the "Lärchenhaus" (fig.) in 1919 - when his partner Erna Schilling left Berlin for good and moved in with him in Frauenkirch. Perhaps it served a reminder of their first encounter at a Berlin cabaret at the turn of the year 1911/12.

Prof. Dr. Dr. Gerd Presler

Provenance

When Donald E. Gordon published the first catalogue raisonné of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's paintings in 1968, he only had the aforementioned black-and-white photo of "Tanz im Varieté" from 1920 at his disposal. He had no idea of its impressive dimensions, nor did he know anything about other photos that showed the work - a rare fortunate incidence - "on site" in Kirchner's studio (above fig.). And its location? Unknown. " Whereabouts unknown". The work would not resurface in public until 2024. But where had it been during most of the past century? The handwritten collection inventory of the former owner provides research with the decisive clue: "acquired by Dr. Lili [sic] Fischel from the Gläser [sic] Collection, Eselsfürth Kaiserslautern in 1944".

Avant-garde in Kaiserslautern: the Max Glaeser Collection, Eselsfürth

The collection of commercial councilor Dr. Max Glaeser (fig.) is well known. As early as in 1907, the successful enamel manufacturer from the Kaiserslautern district of Eselsfürth began to amass an impressive collection of German art from the 19th and early 20th centuries, primarily from Munich. It comprised Lenbach and Stuck, Grützner and Thoma, Spitzweg and Liebermann, but initially no Expressionistm. The first collection catalog, written by the art historian Hugo Kehrer in 1922, provides a detailed evaluation (Hugo Kehrer, Sammlung Max Glaeser, Eselsfürth, Munich 1922). When the next collection catalog was published four years later, works by Corinth and Kokoschka (his cityscape "Madrid") had already been added to the collection. Modernism made its entrance (cf.: Edmund Hausen, Die Sammlung Glaeser, Eselsführt, in: Mitteilungsblatt des Pfälzischen Gewerbemuseums 1, 1926, pp. 41-46).

In 1928/29, the architect Hans Herkommer built a Bauhaus-style villa for Max Glaeser in Eselsfürth, a district of Kaiserslautern (fig.). The family residence was also intended to serve as an exhibition venue for the owner's large art collection. Photos of the premises were published in 1929/30, they show the tasteful avant-garde setting, by today's standards modern and contemporary to the last detail, the perfect environment for a presentation of the works of art (fig.). Edvard Munch and Emil Nolde, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Georg Kolbe, Karl Hofer and Max Pechstein were already among the big names in this important collection (fig., cf.: Edmund Hausen and Hermann Graf, Haus und Sammlung Gläser, in: Hand und Maschine 1, 1929, pp. 105-124, and Edmund Hausen, Die Sammlung Max Glaeser, Eselsfürth, in: Der Sammler, no. 2, January 15, 1930, pp. 25f.). And in October 1930, only months before the death of the then severely ill industrialist, Glaeser informed the art dealer Thannhauser that he wanted to sell the collection with the intention of only acquiring works by modern artists (Zentralarchiv des internationalen Kunsthandels ZADIK, Cologne, A 77, estate of Thannhauser, XIX 0063: client file Glaeser).

Kirchner and Max Glaeser

Two works by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner also became part of the Glaeser Collection around 1930/31. One of them had long been known: "Frühlingslandschaft" (Spring Landscape), today part of the collection of the Pfalzgalerie in Kaiserslautern (fig.). The second Kirchner painting in Glaeser's collection is now on public display for the first time in a century: "Tanz im Varieté".

"Tanz im Varieté" certainly entered the Glaeser Collection after 1928, and very likely only after January 1930. The collector visited the artist in Davos as early as in 1928, apparently encouraged by his advisor, the important art historian Gustav Hartlaub. Glaeser did not buy anything, and Kirchner was notably displeased with the visit (fig.). Glaeser's first acquisition of a Kirchner painting was the 70 by 90 centimeter "Frühlingslandschaft", which found mention as "Landschaft mit Blütenbäumen" (Landscape with Blossoming Trees) in the last contemporary collection catalog published in January 1930 - while "Tanz im Varieté" had not yet been included.

In 1935, four years after Glaeser's death, his widow Anna wanted to sell the collection in various places. The reason behind the urgency is unclear, but it clearly had nothing to do with Nazi dictatorship. The Protestant Glaeser family were not among those persecuted by the regime.

On the occasion of the numerous sales in 1935, Kirchner also recalled the 1928 visit. He told Hagemann that Glaeser had not purchased anything during his stay in Davos, but that he had later bought the painting "Artisten" from an art dealer, which he, Kirchner, could not identify: Glaeser "bought the painting Artists from an art dealer, not from me, and I don't know which one it is". (November 19, 1935, Kirchner to Hagemann, in: Hans Delfs (ed.), Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff, Nolde, Nay ... Briefe an den Sammler und Mäzen Carl Hagemann 1906-1940, Ostfildern 2004, Letter 642, p. 502). What he probably meant here was "Tanz im Varieté".

But why did Max Glaeser choose this particular painting, which is so special in terms of format, color scheme and choice of motif? An anecdote shared by the collector's family should at least be mentioned here: Max Glaeser, who traveled a lot for work, saw a performance by Josefine Baker in Paris. He even danced with her on stage (photographs documenting that evening are lost). Perhaps it was the memory of a special evening in Paris that was behind Max Glaeser's decision to buy "Tanz im Varieté".

In Glaeser's Estate: 1931-1944

When Max Glaeser died in May 1931, "Tanz im Varieté" was part of his legal estate. On September 29 of the same year, the administrator of his estate offered it to the public collection 'Kunstsammlung Basel' as "Varietészene". In the spring and summer of 1932, the painting was on consignment at Galerie Buck in Mannheim, and correspondence with the Basel museum has been preserved. Despite the conservator's now genuine interest in both Kirchner paintings from the Glaeser estate, which were offered with considerable prices of 2,800 Reichsmarks for "Frühlingslandschaft" and 5,500 Reichsmarks for "Tanz im Varieté", a purchase was never realized. Neither with the Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf, to whom Galerie Buck also offered the painting in 1932.

"Tanz im Varieté" remained in the possession of the widow Anna Glaeser, the last written record of it can be found in a collection inventory from February 1943. Anna Glaeser died in February 1944, almost exactly a year after this collection had been listed, and the remaining inventory - ten paintings, mainly by modern artists such as Pechstein, Schmidt-Rottluff, Feininger and Heckel, as well as two sculptures by Kolbe - was distributed among her grandchildren. "Tanz im Varieté" was on the distribution list, but was no longer assigned to an heir, instead it had got a check mark - the work was sold.

Sale and Salvage: 1944-2024

This is where the story the buyer's family tells takes over and completes the history of "Tanz im Varieté".

The new owner was a jewelry designer from Baden, born in 1905, who kept in touch with his avant-garde circle of friends as best he could during the war years. Among them was Lilli Fischel, who had been dismissed from the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe on account of her Jewish origins. She went into hiding in Munich and kept her head above water as free-lancer for Galerie Günther Franke. Lilli Fischel organized the purchase of "Tanz im Varieté" in 1944. In March 1944, she wrote to the art dealer Ferdinand Möller, presumably with reference to the same transaction: "Wouldn't you perhaps have a good painting by Kirchner for sale, like the ones I saw in your gallery in the past? A friend of mine, a keen expert, would like one" (Berlinische Galerie, Ferdinand Möller estate, BG-GFM-C,II 1,169).

It is no coincidence that Lilli Fischel finds her friend a painting from the Glaeser estate. After all, she had known the collection quite well for a long time: Max Glaeser had tried to sell the bulk of his paintings to a museum in 1930 at a point when he already was in poor health. This way the collector wanted to preserve his collection for future generations. He was also in contact with Lilli Fischel, at that time working for the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, about this. On October 20, 1930, the art dealer Thannhauser noted the following about a conversation with the collector: "Miss Fischel, from the Karlsruhe Museum, offered him 150,000 marks for it, while reserving the right to sell parts of it, as not everything was suitable for her museum. He is quite displeased with her because of this poor offer" (Zentralarchiv des internationalen Kunsthandels ZADIK, Cologne, A 77, estate Thannhauser, XIX 0063: client file Glaeser). Hence it stands to reason that Lilli Fischel, in search of a suitable Kirchner painting for her friend, contacted the heirs of the Glaeser Collection. This is how the painting ended up with the jewelry designer. From an early stage, he was enthusiastic about avant-garde art like Expressionism and Bauhaus. From 1923 to 1927, he trained at the Art Students League in New York alongside Alexander Calder, before he went on to spend a year in Paris to deepen his studies.

In 1944, however, such a purchase was not without difficulties. Where to put the monumental work by a "degenerate" artist, how to protect it from air raids and the National Socialist authorities in the midst of World War II? The painting was thought to be safe at a farm in the countryside where it was kept in a heavy duty crate. However, when French troops took the village in 1945, the crate was discovered and forced open. The canvas was damaged by a bullet and a stab with the bayonet: A bullet hit the head of one of the female dancers on the left while the the male dancer's torso was pierced. Fortunately, the soldiers, left the crate with the painting behind. In this way, a highly significant piece of German art history could was rescued. After the war, the painting was expertly restored at the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe by Verena Baier (fig.), once again with the help of Lilli Fischel. Today, the war damages are only visible on the work's reverse side and make the historic events tangible. To this day, "Tanz im Varieté" has remained in the family of the 1944 buyer. In 1980, on the occasion of his 75th birthday, the collector gave the painting to his two children. With this gift, however, he also assigned them the task of returning the painting to the public, for which the artist himself had also intended it. This special legacy from a special collector enables us to rediscover this work of art today. More than 100 years have passed since the painting was last published. Now it is back. "Tanz im Varieté" can finally take its rightful place in art history.

Dr. Agnes Thum

19

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Tanz im Varieté, 1911.

Oil on canvas

Estimation:

€ 2,000,000 / $ 2,320,000 Résultat:

€ 6,958,000 / $ 8,071,279 ( frais d'adjudication compris)

Lot 19

Lot 19