Vente: 550 / Evening Sale 07 juin 2024 à Munich  Lot 124000250

Lot 124000250

Lot 124000250

Lot 124000250

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

Autre image

124000250

James Rosenquist

Playmate, 1966.

Oil on canvas in four parts, wood, metal wire

Estimation: € 1,000,000 / $ 1,070,000

Les informations sur la commission d´achat, les taxes et le droit de suite sont disponibles quatre semaines avant la vente.

Playmate. 1966.

Oil on canvas in four parts, wood, metal wire.

244 x 535 cm (96 x 210.6 in).

• Striking eroticism in an oversized format: Rosenquist's work for Playboy magazine in 1967, from the heyday of American pop art.

• Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselman, George Segal and others also took part in the "Playmate as Fine Art" campaign.

• Rosenquist's four-part work depicts a very special desire, the cravings of a pregnant Playmate for food.

• As early as the 1960s, the art critic Lucy Lippard counted him among the "New York Five", the most important representatives of American pop art (Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselmann, James Rosenquist und Claes Oldenburg).

• Works from this period are among the artist's most sought-after pieces on the international auction market (source: artprice.com).

Accompanied by a photo certificate signed by the artist from 1966.

The work is registered at the archive of Estate of James Rosenquist, New York, with the number "66.10".

PROVENANCE: Playboy Enterprises, Inc., Chicago.

Peter Raczeck Fine Art, New York.

Private collection Southern Germany.

EXHIBITION: Beyond Illustration: The Art of Playboy, travelling exhibition, Central Museum of Art, Tokyo, February 13 - March 11, 1973, Umeda Kindai Museum, Osaka, March 15 - April 8, 1973, Bunda Kaikan, Fukuoka, May 15 - 26, 1973, Lowe Museum of Art, University of Miami, Coral Gables, July 25 - September 9, 1973, Florida State University, Tallahassee, October 8 - November 11, 1973, Morgan State College, Murphy Fine Arts Center, Baltimore, December 2 - 22, 1973, Philadelphia Art Alliance, Philadelphia, February 8 - March 3, 1974, Municipal Art Gallery, Los Angeles, March 26 - April 28, 1974, Syntex Art Gallery, Palo Alto, May 19 - July 15, 1974, New York Cultural Center, New York, August 10 - September 20, 1974.

The Art of Playboy: From the First 25 Years, travelling exhibition, Alberta College of Art Gallery, Calgary, November 12 - 28, 1976, Saskatoon Gallery and Conservatory Corporation, Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, February 9 - March 6, 1977, Priebe Gallery, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh, March 2 - 28, 1978, Art Institute of Atlanta, Atlanta, Aug. 1978, Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, December 19, 1978 - January 20, 1979, Auburn University, Auburn, February 12 - March 12, 1979, Colorado Institute of Art, Denver, June 1979, Art Institute of Ft. Lauderdale, Ft. Lauderdale, Nov. 1979, University of Michigan-Flint, Flint, Jan. 1980, Mulvane Art Center, Washburn University, Topeka, Jan. 1980, Daytona Beach Community College, Daytona Beach, Sept. 1980, Oklahoma Arts Center, Oklahoma City, October 24 - November 28, 1980, University of Wisconsin, Plattsville, February 16 - March 14, 1981, Museum at Sao Paolo, Sao Paolo, March 22 - May 13, 1981, Rio Palace Hotel Gallery, Rio de Janeiro, May 20 - June 3, 1981.

Image World: Art and Media Culture, Whitney Museum of American Art, November 8, 1989 - February 18, 1990, New York, p. 211 (titled "Playmate", with the exhibition label on the reverse).

The Figure and Dr. Freud, Haunch of Venison, New York, July 8 - August 22, 2009.

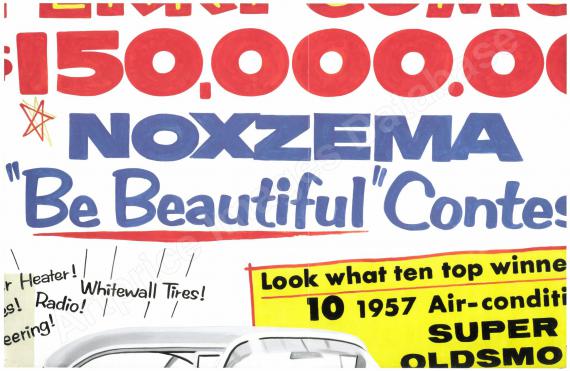

LITERATURE: The Playmate as Fine Art, Playboy Magazine, vol. 14, no. 1, Jan. 1967, pp. 141-149 (color illu. on pp. 146f.).

Gene Swenson, The Figure a Man Makes (Part I), Art and Artists 3, no. 1, April 1968, pp. 26-29, here p. 29.

Michael Compton, Pop Art. Movements of Modern Art, London, New York, Sydney, Toronto, 1970, p. 110 (illu.).

Beyond Illustration: The Art of Playboy, with an introduction by Arthur Paul, Chicago 1971 (illu.).

Evelyn Weiss, James Rosenquist: Gemälde-Räume-Graphik, Cologne 1972, p. 128.

The Art of Playboy: From the First 25 Years, with an introduction by Ted Hearne, Chicago 1978 (illu.).

Ray Bradbury, The Art of Playboy, Alfred van der Marck Editions, New York 1985 (illu. pp. 76f.).

Walter Hopps, Sarah Bancroft, James Rosenquist: A Retrospective, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York 2003, p. 375.

Ingrid Sischy, Rosenquist's Big Picture, Vanity Fair, no. 513, May 2003, here p. 229.

Karen Rosenberg, Art in Review: The Figure and Dr. Freud, The New York Times, August 14, 2009.

James Rosenquist, David Dalton, Painting Below Zero: Notes on a Life in Art, New York 2009, p. 174.

Dave Hickey, The Playmate as Pop Art, Playboy Magazine, vol. 59, no. 5. June 2012, pp. 76-79 (illu. p. 79).

"I consider myself an American artist: I grew up in America, I was concerned about America..I wouldn't be who I am, wouldn't do what I do, if I had lived in France or Italy."

James Rosenquist, quoted from: Kritisches Lexikon der Gegenwartskunst, vol. 48, issue 32, 1999.

Oil on canvas in four parts, wood, metal wire.

244 x 535 cm (96 x 210.6 in).

• Striking eroticism in an oversized format: Rosenquist's work for Playboy magazine in 1967, from the heyday of American pop art.

• Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselman, George Segal and others also took part in the "Playmate as Fine Art" campaign.

• Rosenquist's four-part work depicts a very special desire, the cravings of a pregnant Playmate for food.

• As early as the 1960s, the art critic Lucy Lippard counted him among the "New York Five", the most important representatives of American pop art (Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselmann, James Rosenquist und Claes Oldenburg).

• Works from this period are among the artist's most sought-after pieces on the international auction market (source: artprice.com).

Accompanied by a photo certificate signed by the artist from 1966.

The work is registered at the archive of Estate of James Rosenquist, New York, with the number "66.10".

PROVENANCE: Playboy Enterprises, Inc., Chicago.

Peter Raczeck Fine Art, New York.

Private collection Southern Germany.

EXHIBITION: Beyond Illustration: The Art of Playboy, travelling exhibition, Central Museum of Art, Tokyo, February 13 - March 11, 1973, Umeda Kindai Museum, Osaka, March 15 - April 8, 1973, Bunda Kaikan, Fukuoka, May 15 - 26, 1973, Lowe Museum of Art, University of Miami, Coral Gables, July 25 - September 9, 1973, Florida State University, Tallahassee, October 8 - November 11, 1973, Morgan State College, Murphy Fine Arts Center, Baltimore, December 2 - 22, 1973, Philadelphia Art Alliance, Philadelphia, February 8 - March 3, 1974, Municipal Art Gallery, Los Angeles, March 26 - April 28, 1974, Syntex Art Gallery, Palo Alto, May 19 - July 15, 1974, New York Cultural Center, New York, August 10 - September 20, 1974.

The Art of Playboy: From the First 25 Years, travelling exhibition, Alberta College of Art Gallery, Calgary, November 12 - 28, 1976, Saskatoon Gallery and Conservatory Corporation, Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, February 9 - March 6, 1977, Priebe Gallery, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh, March 2 - 28, 1978, Art Institute of Atlanta, Atlanta, Aug. 1978, Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, December 19, 1978 - January 20, 1979, Auburn University, Auburn, February 12 - March 12, 1979, Colorado Institute of Art, Denver, June 1979, Art Institute of Ft. Lauderdale, Ft. Lauderdale, Nov. 1979, University of Michigan-Flint, Flint, Jan. 1980, Mulvane Art Center, Washburn University, Topeka, Jan. 1980, Daytona Beach Community College, Daytona Beach, Sept. 1980, Oklahoma Arts Center, Oklahoma City, October 24 - November 28, 1980, University of Wisconsin, Plattsville, February 16 - March 14, 1981, Museum at Sao Paolo, Sao Paolo, March 22 - May 13, 1981, Rio Palace Hotel Gallery, Rio de Janeiro, May 20 - June 3, 1981.

Image World: Art and Media Culture, Whitney Museum of American Art, November 8, 1989 - February 18, 1990, New York, p. 211 (titled "Playmate", with the exhibition label on the reverse).

The Figure and Dr. Freud, Haunch of Venison, New York, July 8 - August 22, 2009.

LITERATURE: The Playmate as Fine Art, Playboy Magazine, vol. 14, no. 1, Jan. 1967, pp. 141-149 (color illu. on pp. 146f.).

Gene Swenson, The Figure a Man Makes (Part I), Art and Artists 3, no. 1, April 1968, pp. 26-29, here p. 29.

Michael Compton, Pop Art. Movements of Modern Art, London, New York, Sydney, Toronto, 1970, p. 110 (illu.).

Beyond Illustration: The Art of Playboy, with an introduction by Arthur Paul, Chicago 1971 (illu.).

Evelyn Weiss, James Rosenquist: Gemälde-Räume-Graphik, Cologne 1972, p. 128.

The Art of Playboy: From the First 25 Years, with an introduction by Ted Hearne, Chicago 1978 (illu.).

Ray Bradbury, The Art of Playboy, Alfred van der Marck Editions, New York 1985 (illu. pp. 76f.).

Walter Hopps, Sarah Bancroft, James Rosenquist: A Retrospective, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York 2003, p. 375.

Ingrid Sischy, Rosenquist's Big Picture, Vanity Fair, no. 513, May 2003, here p. 229.

Karen Rosenberg, Art in Review: The Figure and Dr. Freud, The New York Times, August 14, 2009.

James Rosenquist, David Dalton, Painting Below Zero: Notes on a Life in Art, New York 2009, p. 174.

Dave Hickey, The Playmate as Pop Art, Playboy Magazine, vol. 59, no. 5. June 2012, pp. 76-79 (illu. p. 79).

"I consider myself an American artist: I grew up in America, I was concerned about America..I wouldn't be who I am, wouldn't do what I do, if I had lived in France or Italy."

James Rosenquist, quoted from: Kritisches Lexikon der Gegenwartskunst, vol. 48, issue 32, 1999.

James Rosenquist in New York - Hotspot of American Pop Art

In the 1960s, Pop Art, which hade established a new style modeled on mass media, saw a boom in North America, especially in New York, where a scene had grown around the galleries of Leo Castelli, Richard Bellamy and Sidney Jannis. James Rosenquist was one of the main protagonists.

In the mid-1950s, the North Dakota-born art student came to New York on a scholarship from the Art Students League. Making a living as a poster painter earned him the nickname "Billboard Michelangelo". When two of his colleagues fell from the scaffolding and died, he quit and decided to pursue a career in art. In 1960, he moved into a studio in the south of Manhattan in the immediate vicinity of artists such as Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Indiana and Jack Youngerman. He soon caused a stir in the local art scene with his unusually large-format works and depictions of hugely enlarged details, which were influenced by his experience as a poster painter.

Richard Bellamy's Green Gallery showed his first solo exhibition in 1962, and shortly afterwards he signed with the important gallerist Leo Castelli. In 1965, one of his works was exhibited at the Castelli gallery, and he became famous overnight. "F 111" measures 3 x 26 meters and covers the entire exhibition space in the front room of the gallery. The initial plan was to sell the 51 pieces separately, but Robert Scull, art collector and owner of the largest cab fleet in New York, ended up buying the entire work. Scull is quoted in the New York Times saying: "We are considering lending the work to institutions because it is the most important statement in art in 50 years." (Robert Scull, in: Richard F. Shepard, "To What Lengths Can Art Go?", New York Times, May 13, 1965, quoted from: James Rosenquist Studio, online: www.jamesrosenquiststudio.com/artist/chronology) In 1978, the painting was shown at the 38th Venice Biennale, today it is in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Over the course of just a few years, James Rosenquist had gone from being a broke poster painter to one of the most sought-after artists of his time.

In 1966, the year James Rosenquist's "Playmate" was created, art critic Lucy R. Lippard published the first monograph on the new art movement and identified the most important representatives of the latest trends as the "The New York Five": Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselmann, James Rosenquist und Claes Oldenburg (cf. Lucy R. Lippard, Pop Art, London 1966, p. 69). James Rosenquist designed the cover of the publication. At tha time the movement was widely publicized and addressed in numerous panel discussions and interviews, the artists received accolades and were shown in major museum exhibitions around the world. Pop Art spread from New York at breakneck speed within a few years, successfully replacing Abstract Expressionism and soon dominating the 1960s art scene.

In some respects, the artistic approaches of the representatives of Pop Art differ significantly. However, everyday culture and the integration of mass media into the visual language of high culture, which had previously tried to distance itself from popular trends, remained their most important common feature. In 1965, the American critic Gene R. Swenson expressed the need for this change: "We have to deal with the most common clichés and the most stereotypical reactions if we are to come to an understanding of the potential this brave and not entirely hopeless new world offers us." (Quoted from: Hubertus Butin (ed.), Begriffslexikon zur zeitgenössischen Kunst, Cologne 2002, p. 245) With a background in poster painting, James Rosenquist was the ideal man to shape a new style based on the tastes of the masses. His formats were large right from the start, the forms reduced and striking, the colors bright and vibrant, the themes known from magazines and the media. He experimented with different materials, integrating everyday objects into his paintings or choosing plastic slats as a support for his pictures, which he installed as free-standing, three-dimensional objects in the room. In 1966, he took part in the "Peace Tower", an 18-meter-high tower of artworks erected in Hollywood as a protest against the Vietnam War. In the same year, he had a suit made from Kleenex wrapping paper by fashion designer Horst, which he wore at exhibition openings. Looking back, James Rosenquist once described the 1960s as a "non-stop party" and the following 70s as a "terrible hangover" (cf. Thomas Zacharias about James Rosenquist, in: Kritisches Lexikon der Gegenwartskunst, vol. 48, issue 32, 1999, p. 10).

The male gaze? James Rosenquist's "Playmate" from 1966

In this pulsating cultural environment, the Chicago-based men's magazine "Playboy" launched the "Playmate as Fine Art" campaign in 1966. A total of 11 artists were invited to transfer the "idea" of the Playmate into art. The works that were especially made for the campaign were shown in the January 1967 issue. In addition to James Rosenquist, Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann, George Segal and Larry Rivers also took part in the campaign. Ellen Lanyon was the only female artist in the otherwise male dominated group. In the caption to her work we read: "..our only female contributor, Miss Lanyon saw the Playmate..poetically in cahoots with the moon, away from men.." (For quotes from Playboy magazne see: The Playmate as Fine Art, Playboy Magazine, vol. 14, no. 1, Jan. 1967, pp. 141-149). The men's magazine declared Andy Warhol America's Prince of Pop. His contribution shows the naked double torso of a Playmate, which only becomes visible under ultraviolet light, "to keep the cops away", as Warhol is said to have remarked. Tom Wesselman created a large female mouth with white teeth and bright red lipstick. Larry Rivers, as it is said with a quiet undertone, "had taken the commission very seriously". He submitted an almost life-size, semi-nude female figure made of Plexiglas and metal in predominantly red and pink. Just like the other contributions, James Rosenquist's "Playmate" is also quickly explained. In a huge format of 244 x 535 cm, he shows a naked female torso in the center of the picture, with a gherkin to the right, a strawberry cake to the left, and the grid structure of a paper basket in front of it. Sexual connotations and symbols are difficult to deny in a striking composition so typical of the artist. However, he wrote about the work in his autobiography: "I painted Playmate, a pregnant girl suffering from food cravings." (James Rosenquist, Painting Below Zero, New York 2009, p. 174). With just one short sentence, he unexpectedly questions the entire reception of the work and our stereotypical viewing habits. The initially exclusively male "idea" of the Playmate, is reversed, because what he shows, or says he wants to show, is a very female desire, not a male one.

However, seeing the work as an outcry against Playboy's image of women would be too far-fetched. Rosenquist's involvement in the project coincided with a time of major success and should be understood more as a humorous occasion. In contrast to Warhol or Wesselmann, who usually concentrate on a single motif, Rosenquist's combination of different elements, once so aptly described by Ingrid Sischy as "alchemy with images" (Ingrid Sischy, Rosenquist's Big Picture, Vanity Fair, Nov. 2015), allows for a certain scope of nuances. For example, the idea behind the silver wastepaper basket remains unclear and the addition of wooden and wire elements to the canvas cannot be interpreted beyond doubt. It almost seems as if his Playmate does not quite fit into the rectangular, stereotypical shape of the canvas. As is so often the case with Rosenquist, his Playmate is only superficially striking and more than a mere reproduction of a media image.

The introduction to "Playmate as Fine Art" in Playboy magazine contains a statement by the editor Hugh M. Hefner: "..there is no doubt that the girls have become a fact in this generation's consciousness, an embodiment of a new feeling toward the female, an American phenomenon". Rosenquist's work is therefore also about the confrontation with American aesthetics and an ideal of female beauty that would become established internationally only in subsequent decades. Even if this image of women is questionable from today's perspective, the Playboy's campaign reflects the zeitgeist of the 1960s, when Pop Art saw its international breakthrough. James Rosenquist once said: "I consider myself an American artist: I grew up in America, I thought about America, I wouldn't be who I am, I wouldn't do what I do, if I had lived in France or Italy." (James Rosenquist, quoted from: Kritisches Lexikon der Gegenwartskunst, vol. 48, issue 32, 1999) His Playmate with food cravings is a product of this time, a humorous, erotically tingling creation with quiet overtones and at the same time a testimony to one of the most important art movements of the second half of the 20th century. [AR]

In the 1960s, Pop Art, which hade established a new style modeled on mass media, saw a boom in North America, especially in New York, where a scene had grown around the galleries of Leo Castelli, Richard Bellamy and Sidney Jannis. James Rosenquist was one of the main protagonists.

In the mid-1950s, the North Dakota-born art student came to New York on a scholarship from the Art Students League. Making a living as a poster painter earned him the nickname "Billboard Michelangelo". When two of his colleagues fell from the scaffolding and died, he quit and decided to pursue a career in art. In 1960, he moved into a studio in the south of Manhattan in the immediate vicinity of artists such as Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Indiana and Jack Youngerman. He soon caused a stir in the local art scene with his unusually large-format works and depictions of hugely enlarged details, which were influenced by his experience as a poster painter.

Richard Bellamy's Green Gallery showed his first solo exhibition in 1962, and shortly afterwards he signed with the important gallerist Leo Castelli. In 1965, one of his works was exhibited at the Castelli gallery, and he became famous overnight. "F 111" measures 3 x 26 meters and covers the entire exhibition space in the front room of the gallery. The initial plan was to sell the 51 pieces separately, but Robert Scull, art collector and owner of the largest cab fleet in New York, ended up buying the entire work. Scull is quoted in the New York Times saying: "We are considering lending the work to institutions because it is the most important statement in art in 50 years." (Robert Scull, in: Richard F. Shepard, "To What Lengths Can Art Go?", New York Times, May 13, 1965, quoted from: James Rosenquist Studio, online: www.jamesrosenquiststudio.com/artist/chronology) In 1978, the painting was shown at the 38th Venice Biennale, today it is in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Over the course of just a few years, James Rosenquist had gone from being a broke poster painter to one of the most sought-after artists of his time.

In 1966, the year James Rosenquist's "Playmate" was created, art critic Lucy R. Lippard published the first monograph on the new art movement and identified the most important representatives of the latest trends as the "The New York Five": Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselmann, James Rosenquist und Claes Oldenburg (cf. Lucy R. Lippard, Pop Art, London 1966, p. 69). James Rosenquist designed the cover of the publication. At tha time the movement was widely publicized and addressed in numerous panel discussions and interviews, the artists received accolades and were shown in major museum exhibitions around the world. Pop Art spread from New York at breakneck speed within a few years, successfully replacing Abstract Expressionism and soon dominating the 1960s art scene.

In some respects, the artistic approaches of the representatives of Pop Art differ significantly. However, everyday culture and the integration of mass media into the visual language of high culture, which had previously tried to distance itself from popular trends, remained their most important common feature. In 1965, the American critic Gene R. Swenson expressed the need for this change: "We have to deal with the most common clichés and the most stereotypical reactions if we are to come to an understanding of the potential this brave and not entirely hopeless new world offers us." (Quoted from: Hubertus Butin (ed.), Begriffslexikon zur zeitgenössischen Kunst, Cologne 2002, p. 245) With a background in poster painting, James Rosenquist was the ideal man to shape a new style based on the tastes of the masses. His formats were large right from the start, the forms reduced and striking, the colors bright and vibrant, the themes known from magazines and the media. He experimented with different materials, integrating everyday objects into his paintings or choosing plastic slats as a support for his pictures, which he installed as free-standing, three-dimensional objects in the room. In 1966, he took part in the "Peace Tower", an 18-meter-high tower of artworks erected in Hollywood as a protest against the Vietnam War. In the same year, he had a suit made from Kleenex wrapping paper by fashion designer Horst, which he wore at exhibition openings. Looking back, James Rosenquist once described the 1960s as a "non-stop party" and the following 70s as a "terrible hangover" (cf. Thomas Zacharias about James Rosenquist, in: Kritisches Lexikon der Gegenwartskunst, vol. 48, issue 32, 1999, p. 10).

The male gaze? James Rosenquist's "Playmate" from 1966

In this pulsating cultural environment, the Chicago-based men's magazine "Playboy" launched the "Playmate as Fine Art" campaign in 1966. A total of 11 artists were invited to transfer the "idea" of the Playmate into art. The works that were especially made for the campaign were shown in the January 1967 issue. In addition to James Rosenquist, Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann, George Segal and Larry Rivers also took part in the campaign. Ellen Lanyon was the only female artist in the otherwise male dominated group. In the caption to her work we read: "..our only female contributor, Miss Lanyon saw the Playmate..poetically in cahoots with the moon, away from men.." (For quotes from Playboy magazne see: The Playmate as Fine Art, Playboy Magazine, vol. 14, no. 1, Jan. 1967, pp. 141-149). The men's magazine declared Andy Warhol America's Prince of Pop. His contribution shows the naked double torso of a Playmate, which only becomes visible under ultraviolet light, "to keep the cops away", as Warhol is said to have remarked. Tom Wesselman created a large female mouth with white teeth and bright red lipstick. Larry Rivers, as it is said with a quiet undertone, "had taken the commission very seriously". He submitted an almost life-size, semi-nude female figure made of Plexiglas and metal in predominantly red and pink. Just like the other contributions, James Rosenquist's "Playmate" is also quickly explained. In a huge format of 244 x 535 cm, he shows a naked female torso in the center of the picture, with a gherkin to the right, a strawberry cake to the left, and the grid structure of a paper basket in front of it. Sexual connotations and symbols are difficult to deny in a striking composition so typical of the artist. However, he wrote about the work in his autobiography: "I painted Playmate, a pregnant girl suffering from food cravings." (James Rosenquist, Painting Below Zero, New York 2009, p. 174). With just one short sentence, he unexpectedly questions the entire reception of the work and our stereotypical viewing habits. The initially exclusively male "idea" of the Playmate, is reversed, because what he shows, or says he wants to show, is a very female desire, not a male one.

However, seeing the work as an outcry against Playboy's image of women would be too far-fetched. Rosenquist's involvement in the project coincided with a time of major success and should be understood more as a humorous occasion. In contrast to Warhol or Wesselmann, who usually concentrate on a single motif, Rosenquist's combination of different elements, once so aptly described by Ingrid Sischy as "alchemy with images" (Ingrid Sischy, Rosenquist's Big Picture, Vanity Fair, Nov. 2015), allows for a certain scope of nuances. For example, the idea behind the silver wastepaper basket remains unclear and the addition of wooden and wire elements to the canvas cannot be interpreted beyond doubt. It almost seems as if his Playmate does not quite fit into the rectangular, stereotypical shape of the canvas. As is so often the case with Rosenquist, his Playmate is only superficially striking and more than a mere reproduction of a media image.

The introduction to "Playmate as Fine Art" in Playboy magazine contains a statement by the editor Hugh M. Hefner: "..there is no doubt that the girls have become a fact in this generation's consciousness, an embodiment of a new feeling toward the female, an American phenomenon". Rosenquist's work is therefore also about the confrontation with American aesthetics and an ideal of female beauty that would become established internationally only in subsequent decades. Even if this image of women is questionable from today's perspective, the Playboy's campaign reflects the zeitgeist of the 1960s, when Pop Art saw its international breakthrough. James Rosenquist once said: "I consider myself an American artist: I grew up in America, I thought about America, I wouldn't be who I am, I wouldn't do what I do, if I had lived in France or Italy." (James Rosenquist, quoted from: Kritisches Lexikon der Gegenwartskunst, vol. 48, issue 32, 1999) His Playmate with food cravings is a product of this time, a humorous, erotically tingling creation with quiet overtones and at the same time a testimony to one of the most important art movements of the second half of the 20th century. [AR]

124000250

James Rosenquist

Playmate, 1966.

Oil on canvas in four parts, wood, metal wire

Estimation: € 1,000,000 / $ 1,070,000

Les informations sur la commission d´achat, les taxes et le droit de suite sont disponibles quatre semaines avant la vente.